Meditation Apps and the Unbearable Whiteness of Wellness

Meditation Apps and the Unbearable Whiteness of Wellness

ABSTRACT

This field review provides a critical history and overview of the two most popular for-profit meditation apps, Calm and Headspace, which have seen a dramatic uptick in downloads in the wake of Covid-19. I use these apps as case studies to critique what is sometimes called the “wellness-industrial complex”: the multibillion-dollar industry that caters to overwhelmingly white and affluent consumers, often through the appropriation and decontextualization of non-Western spiritual and medicinal practices. As I argue, wellness apps look, sound, and move in a way that claims to be deracinated, but in fact capitalize on a disembodied form of default whiteness by framing personal wellbeing as a fundamentally apolitical enterprise. By looking to the visual, haptic, and auditory design of for-profit meditation apps—and the normative racialized, class-based, and gendered markers they enforce—I show how a sanitized version of “Eastern philosophies,” particularly Zen Buddhism, have become an alibi for the large-scale abandonment of care for those who need it the most. I conclude with some alternative possibilities for how meditation apps might approach the question of wellness by ceasing to erase the political realities of the world.

At the University of Michigan, where I currently work, there are signs scattered around campus reading “Have you checked on your well-being lately?” Accompanied by a childlike, whimsical cartoon of a colorful anthropomorphized starburst with wide eyes and a smile (see figures 1a-b), the signs feature a QR code leading you to wellbeing.umich.edu, which lists available resources on campus intended to reduce stress. In the main library, there is a lounge area with cushioned chairs and a series of flat screens announcing: “Sign up to Take a Break!”, “Introduction to Tai Chi,” “Self-Massage: Neck and Shoulders,” and “Body Scan Meditation” (see figures 2a-b). In their frequent use of the second person, as well as the emphasis on self-motivation (even massages are self-administered!), UM’s Well-being Collective and other institutionalized wellness initiatives outsource care responsibility to the individual. They are Band-Aid solutions that allow systemic change to remain indefinitely deferred.

Photo by author.

Photo by author.

Photo by author.

Photo by author.

We’re surrounded by examples of institutionalized wellness as performative care. In March 2021, Amazon launched their “WorkingWell” initiative, which included patented “AmaZen” stations or “Zenbooths”—individual kiosks where employees could watch meditation videos or listen to positive affirmations without having to leave the warehouse (Amazon 2021). In all these instances, wellness is merely a pause rather than a full stop in the gears of productivity and innovation (see Zuckerbrod 2022). Many corporate wellness initiatives use a carrot-and-stick model, offering financial incentives like penalty fees (the stick) or reduced insurance premiums (the carrot) to those who opt into these programs. But to even qualify for programs like Whole Foods’ now-infamous Team Member Healthy Discount Incentive Program (Ward 2023), employees must meet certain bodily metrics. The BMI (body mass index), which sets the standard for what is considered “overweight,” “obese,” and “morbidly obese,” is the go-to barometer of wellness in most of these programs, despite being based on antiquated data that contributes to the stigmatization of larger bodies—particular those belonging to Black and Brown people (see Strings 2019).[1]Incidentally, though recent lawsuits have been filed stating that workplace wellness initiatives violate the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act … Continue reading Ultimately, workplace wellness programs can have detrimental or even punitive effects on those who are not white, thin, and able-bodied or who don’t already have access to high-quality healthcare (Nopper and Zelickson 2023). These initiatives offload the labor of care onto those in the most precarious positions, for whom monitoring their eating and exercise, even massaging their own bodies in public, becomes a personal responsibility.

Since the pandemic, mental healthcare has become increasingly digitally mediated (Zeavin 2021). Meditation and mindfulness apps, which often play an important role in workplace wellness programs, are a particularly striking example of the appification of mental health and its embroilment within what is sometimes called “the wellness-industrial complex” (Gunter 2018). These wellness apps, designed primarily for smartphones, nudge users toward a supposedly contemplative and healthy relationship to their devices that breaks with the commonly held notion that phones are distracting or detrimental to restfulness and mental wellbeing. The paradox, of course, is that users must cultivate this state of inner calm by becoming increasingly dependent on a touchscreen interface.

Here, I analyze the visual, haptic, and auditory features of the two most downloaded meditation and mindfulness apps in the United States, Headspace and Calm (both are valued at over $2 billion and both require a paid subscription of $69.99 per year).[2]In April 2020, 3.9 million new users installed Calm on their phones, with Headspace coming in second with 1.5 million installs (see Chapple 2020). Their interfaces differ aesthetically; Calm uses photorealistic imagery while Headspace has become known for a distinctive style of whimsical, childlike animation featuring simple shapes and bright colors. However, both design strategies involve a high degree of abstraction in which “real” humans are rarely present and environmental metaphors abound. They construct a pretechnological utopia in which political strife, economic inequality, and racial and bodily difference are as elusive as the clouds that populate the platforms’ digital skies.

This promise of a diluted imaginary Asianness that is somehow more “natural” and less corrupt than its Western counterpart obscures the wellness industry’s abandonment of responsibility for both mental and physical health care for those who need it the most.

Though these apps look, sound, and move in a way that claims to be deracinated and apolitical, I argue that they are in fact designed for an assumed white user while capitalizing on the appropriation and decontextualization of non-Western spiritual and curative practices (particularly Zen Buddhism). This promise of a diluted imaginary Asianness that is somehow more “natural” and less corrupt than its Western counterpart obscures the wellness industry’s abandonment of responsibility for both mental and physical health care for those who need it the most. The depoliticized form of self-care found in mainstream mindfulness apps placates the user, urging them to accept the status quo—“wellness” as synonymous for efficiency and self-optimization—rather than forging collective bonds or enacting tangible social change.

Companies like Calm and Headspace rarely publicize their user demographics; however, recent studies have found that paying Calm subscribers are predominantly female, college-educated, and as much as 80–90 percent white (Bhuiyan et al. 2021; May and Maurin 2021). And although a Headspace subscription is much cheaper than a one-on-one therapy session or an in-person meditation class, most of Headspace’s US users have household assets that exceed six figures, indicating that the app’s reach is limited to a demographic that could easily afford privatized care (Ake 2022). As these statistics would suggest, Headspace and Calm preach inclusivity and universality while catering to a remarkably narrow user base. In what follows, I’ll show how Calm and Headspace’s formal features work in tandem to encode the assumption of whiteness into these digital platforms. In doing so, I ask: What happens when we center our analysis of mindfulness and meditation apps on those whose embodied experiences don’t fit into the default whiteness of culturally mandated understandings of wellness and health? Must digital wellness always be focused on self-optimization, or are there alternatives that escape the confines of the wellness-industrial complex?

Encoded Whiteness

A common critique of meditation apps is that they try to distance themselves from the problematic aspects of ubiquitous computing while capitalizing on the same logic of gamification and data mining (Jablonsky 2022). Ubiquitous computing, as opposed to desktop computing, refers to the capacity for everyday objects (such as smartphones, laptops, wearable devices, and sensors) to communicate with one another as a user moves throughout the world. According to this critique, touchscreen-based wellness apps are more similar than they are different to other forms of mobile computing, making it increasingly difficult for users to avoid having their movements or biometric data tracked by their devices. While this approach is valid, focusing exclusively on Big Data and surveillance capitalism alone omits how mindfulness apps feed into normative understandings of health and wellness that often fall along racial lines. Here, I move beyond the surveillance capitalism critique and look at how these apps capitalize on a disembodied form of default whiteness—the racial category disguised as “neutral”—by framing personal wellbeing as a fundamentally apolitical enterprise. To clarify, the way I’m using “whiteness” here is less about identity and representation and more so an underlying structural logic or orientation that persists even in the absence of human figures. This is a whiteness that, following scholars such as Ruha Benjamin and Richard Dyer, is encoded into these technologies on both an aesthetic and an infrastructural level to contain and pacify political resistance from those who deviate from this norm (Benjamin 2019; Dyer 1997).

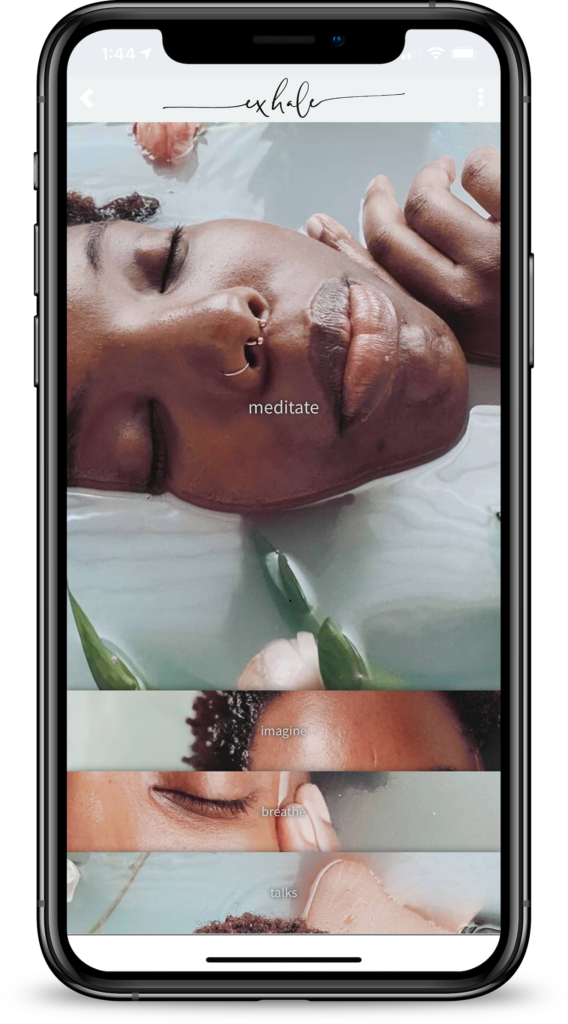

At first glance, it might appear that Headspace and Calm have gestured toward racial diversity by prominently featuring thumbnails of celebrities by the likes of Matthew McConaughey, Harry Styles, LeBron James, and Priyanka Chopra Jonas, who lead guided meditations and “sleep stories.” Blurring the distinction between entertainment and mindfulness culture, the roster of faces is a United Colors of Benetton-esque campaign of diversity, equity, and inclusion. The massive amount of funding spent to secure celebrity participation suggests that providing a range of diverse (but ultimately ultrarich and successful) faces is central to their platforms.[3]As of 2019, Headspace had secured 75.2 million dollars and some stars are paid as much as $100k per recording session (Laderer 2019). But as we’ll see, this cosmetic diversity does little to change the underlying logic of these apps, which continue to assume the existence of an unmarked—a.k.a. white—user. By contrast, while it might seem that Black and POC-owned apps such as Shine and Exhale operate by a similar logic—including more instructors of color on their platforms—they represent an important break from Calm and Headspace. These apps are not using diversity as a cosmetic solution. Instead, they aim to reconfigure the ideology of wellness itself by repositioning self-care as intrinsically political.

It’s important to stress that mindfulness apps are profoundly ambient and multisensory, a confluence of the haptic, auditory, and visual. These apps heighten the physical sensation of breathing by doing the visualization for the user: On Headspace, a cartoon sun inhales and exhales on loop, encouraging the user to do the same (see figure 3), and on Calm, the concentric circles undulate and instruct the user to “breathe in, breathe out” (see figure 4).

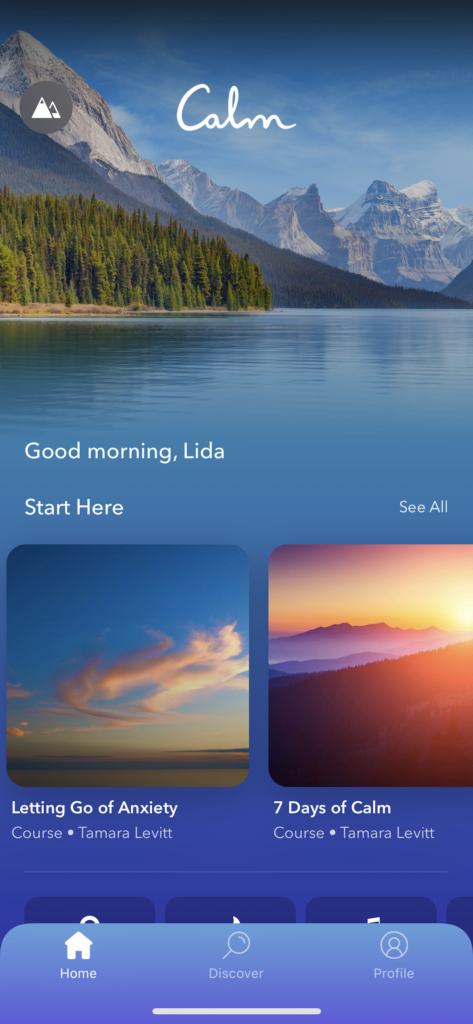

The sonic affordances of mindfulness apps also work to foster a unique intimacy between the user and disembodied voice. Amanda Hess, writing for the New York Times, recounts her increasing dependence on her voice of choice on Calm, which she later discovers belongs to Canadian author and meditation coach Tamara Levitt: “Ours is a strangely intimate relationship. Hers is the last voice that I hear before I go to sleep. She speaks to me past the point that I am even aware that I am hearing anything” (Hess 2019). Mindfulness apps fall under what Neta Alexander calls “soporific media,” or “any medium or feature designed to induce sleep, including noise-canceling sleep headphones, sleep trackers, ASMR videos, the streaming platform Napflix, sleep apps like Calm and Slumber, and endless other products” (Alexander 2023; see Mulvin 2018). Though not all guided meditations on wellness apps are meant for sleep, the design of these platforms habituates users to view their smartphones as self-soothing mechanisms that often find a place next to their pillows. Guided meditations and sleep sounds, which sometimes have no human voice present at all, operate just below the threshold of conscious attention, inducing a desire for the listener to forget the boundaries of their own body or individual circumstances.

Because race is an aural as well as a visual construct, it’s hardly a surprise the typical voice-over of meditation apps, which is meant to go relatively unnoticed but still register as “pleasant” and “soothing” is coded as white (see Stoever 2016 and Eidsheim 2018). Though Headspace now prides itself on featuring an array of “diverse” instructors, until 2019, UK-born Headspace CEO Andy Puddicombe’s voice was the only one available for guided meditations. (That it took until 2020 for the company to bring on meditation instructors of color seems opportunistic, part of a larger trend of performative solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement [Glover 2021].) Even now, Puddicombe’s deep voice and clipped English accent have remained more or less synonymous with the platform. William Fowler, Headspace’s head of content, has described Puddicombe’s voice as “kind of accentless” and “oddly neutral” for US listeners despite his Britishness, but one that nevertheless “manages to express a kindness and approachability” (Glover 2021). But what does or does not constitute a “neutral” accent—there is in fact no such thing—nearly always falls along race and class-based lines. This assumption of whiteness as the unmarked standard thus operates on a sonic as well as a visual level. Beyond these vocal patterns, mindfulness apps often layer instrumental New Age music over the meditation instructor’s voice, signaling a type of “somatic Orientalism” that also helps efface its whiteness by pointing to a nonspecific Eastern locale (Putcha 2020).

Putting the E-Z in Zen

To tell the story of meditation and mindfulness apps is to narrate Silicon Valley’s obsession with a uniquely American construction of “The East”—and, consequently, how non-Western spirituality has become wholly integrated into the rise-and-grind mindset of 24/7 capitalism. We can trace Silicon Valley’s ideological lineage back to the countercultural movements of 1960s and 1970s California, many of which looked to Buddhism, meditation, and psychedelics as a way of liberating one’s consciousness from mainstream society (Turner 2006). Mindfulness apps are part of this lineage. Both Calm and Headspace were originally founded in the 2010s by white, male (and, for some reason, British) entrepreneurs. According to Headspace’s official website, Puddicombe was ordained as a Tibetan Buddhist monk after studying meditation in the Himalayas for ten years, after which he returned to London and opened a private meditation clinic. This more business-oriented endeavor led him to create Headspace in 2010.

Whereas Headspace came about due to Puddicombe’s long-term interest in Buddhism and mindfulness, tech entrepreneurs Michael Acton Smith and Alex Tew cofounded Calm in 2012 in part because the domain calm.com was up for auction. Tew was a regular meditator, but Acton-Smith was skeptical of meditation’s “religious connotations” until he had an epiphany: “Wow, this is actually neuroscience. This is a way of rewiring the human brain. It’s one of the most valuable skills for Western society” (Lowrey 2021). Mindfulness here only gains legitimacy once it becomes subsumed by Western scientific rationalism.

The “Buddhism” in meditation apps functions as a holistic counterpart to the perceived rationality of global network capitalism.

Central to this equation of scientific rationalism with progress is the way in which digital wellness leverages a sanitized version of “Buddhism” as a form of cultural capital. R. John Williams calls this tendency technê-Zen, tracing how corporate capitalism has embraced a watered-down version of Zen Buddhism, alongside other spiritual practices originating in East Asia like Daoism, in order to promote “technological innovation… as yet another path toward enlightenment” (2014, 175).[4]Slavoj Žižek makes a similar argument that global capitalism thrives on the reconciliation of the mythos of the “exotic” Far East with neoliberal ideology (Žižek 2001). As with Amazon’s Zenbooths, the “Buddhism” in meditation apps functions as a holistic counterpart to the perceived rationality of global network capitalism. The outcome for contemporary wellness culture is twofold: On the one hand, Western scientific paradigms give credence to the supposedly “exotic” or irrational practices like Zen, tai chi, or yoga. On the other hand, these same non-Western practices become a panacea for the ills of modern technology, which in turn justify digital capitalism’s relentless march toward “innovation” and “progress.” As part of mindfulness’s merger with self-help culture and other mainstream forms of psychology and therapy, mindfulness in America’s highly individualistic culture also became a tool for self-actualization rather than its original goal: “to awaken transcendental Buddhist insight into no-self and impermanence” (Williams 2014, 113).

buddhify, another popular meditation app, makes no specific reference to Buddhism apart from its name, which turns a spiritual practice into a straightforward “life-hack.” Though founder Rohan Gunatillake is second-generation Sri Lankan and returned to Sri Lanka—a majority Buddhist country—for a meditation sabbatical in his twenties, he speaks openly about how mindfulness’s religious or spiritual associations are a barrier to be overcome and has even gone so far as to reframe Buddhism as “a history of innovation” (2012). In Modern Mindfulness and related public speaking engagements, Gunatillake promotes buddhify as a form of “native Western Buddhism” for users who want to practice “mindfulness on-the-go” (2017). For the quintessential meditation app user—a young urban professional embracing the rise-and-grind lifestyle—the goal is not to stop, but to pause, however briefly, before returning to work. Because appified mindfulness is fully congruous with a white-collar lifestyle, it’s no surprise that corporate management has so enthusiastically promoted it as a way of preventing burnout, which, as Tung-Hui Hu points out, is a uniquely white-collar problem (Hu 2022, xii).

In their focus on self-improvement and professional and personal success, the decontextualized version of “Buddhism” meditation apps promote has less to do with a religion for which the loss of the self has historically played such a central part and more with the depoliticization of wellness writ large. A recent Saturday Night Live sketch singles out how commercialized wellness and politics have become mutually exclusive. Aired in early April 2023 shortly after Donald Trump was indicted, the sketch takes the form of a faux advertisement for a fictional meditation app called “CNZen,” whose interface has obvious resemblances to Calm’s. CNZen finds its target audience in “the most militant liberals,” soothing them with meditations and sleepcasts of CNN anchors and New York Times reporters recounting “sensual details from Trump’s arrest” and providing “Trump indictment ASMR.”

The parody works on several counts. Its humor stems in part from the ludicrous notion that a for-profit meditation app would ever directly reference current events or have an obvious political slant, even though popular news sources routinely run headlines like “Election stress? Here are 8 apps to support your mental health” (Kindelan and Bernabe 2020) and “Ease Your Coronavirus Worries with These Meditation Apps” (Peterson 2020). The fact that the sketch was produced by well-to-do, predominantly white liberals for other well-to-do, predominantly white liberals also does not go unnoticed.) In the same way that statements like “politics doesn’t affect me” or “I’m not into politics” can resonate only with those for whom the system is working, meditation apps urge users to cultivate internal calm regardless of their external reality (“In your mind, he’s already in jail”). And of course, the fact that the faux meditation app is called CNZen points to wellness companies’ pattern of monetizing a vacuous version of “Eastern religion” for maximum gain. By framing mindfulness as a universal coping strategy as well as eradicating racial and bodily difference through graphics and sound, meditation apps construct a particular standard of wellness that allows one to “thrive”—one that is in theory, but not in practice, equally achievable for everyone.

Remember the Blue Sky

One key way in which mindfulness apps have gained traction among secular Western audiences is by promoting self-guided treatments like Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and its derivatives Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT) and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). Adopting these therapeutic techniques gives meditation apps an air of scientific validity that evens out holistic “Eastern” values of ambiguous origin. These three modalities, while initially intended for specific diagnoses (CBT for depression, DBT for borderline personality disorder, and ACT for panic and anxiety), have become increasingly mainstream and depathologized since their emergence in the mid-twentieth century. Headspace Health and Calm Health, offshoots of the two companies, explicitly mention all three modalities on their respective sites accompanied by words like “scientific,” “evidence-based,” and “clinical.” The widespread implementation of these therapies has both negative and positive consequences: On the one hand, self-administered therapies make mental healthcare more widely accessible, since they no longer require a trained professional to be present or a valid insurance plan. At the same time, they also limit treatment outcomes to an enclosed feedback loop of feelings ➡️ behavior ➡️ thoughts that relegates all problems to the patient’s psyche (Zeavin 2021, 153). Like meditation apps, with CBT there is no overarching goal of excavating the roots of these behaviors or situating them in the context of the patient’s lived historical or political reality.

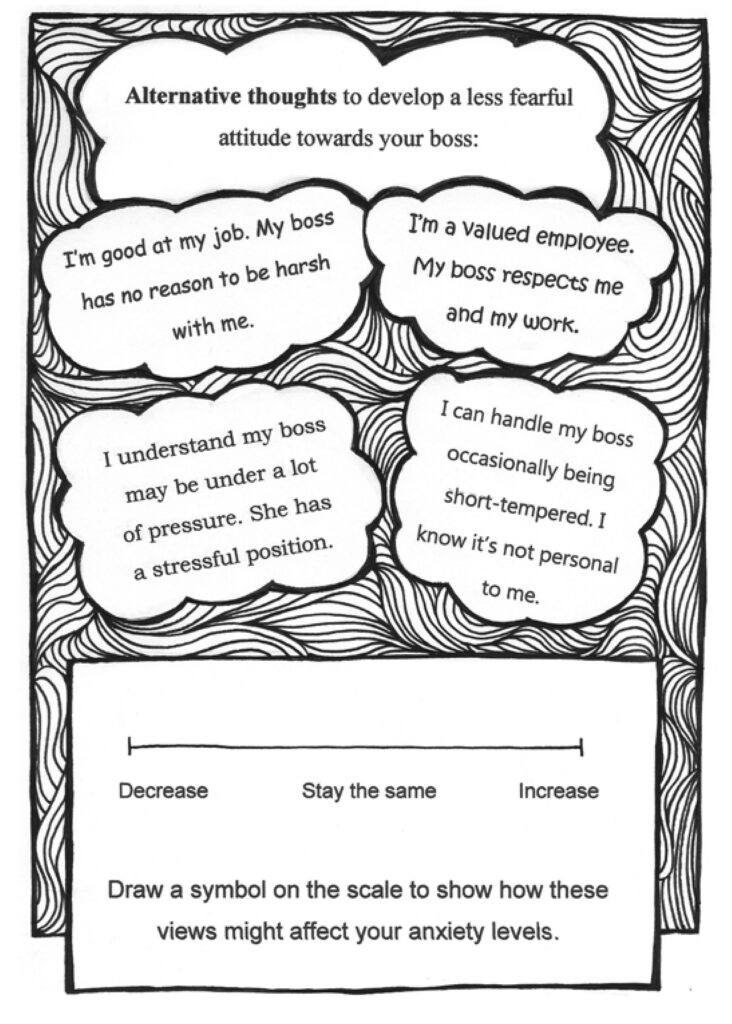

Because of their self-directed nature, CBT and its offshoots are uniquely suited to digital automation, as Hannah Zeavin observes (2021, 153). I would add that this particular brand of Western secular mindfulness has also been compatible with digital interfaces due to its reliance on visual metaphors. The Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Skills Handbook encourages those experiencing intrusive or unpleasant thoughts to visualize each passing thought as billboards on the highway, leaves floating down a stream, or clouds in the sky—a process known as thought defusion. While print media like handbooks and worksheets render thoughts as hand-drawn, black-and-white illustrations that are often meant to be colored in, meditation apps lend themselves to a more immersive experience by introducing color, movement, and sound alongside the intimacy of a hand-held device. For example, The CBT Art Workbook for Coping with Anxiety provides an illustration of possible positive thoughts that could replace fearful ones by rendering them as thought bubbles resembling cartoon clouds (see figure 5). Cross-hatching and shading give the clouds some dimensionality, but—at the risk of making too obvious a point—the clouds don’t move or promise a world beyond the page. By contrast, meditation apps promise to immerse the viewer into a serene expanse by lending movement to still images. This movement is often quite slow and subtle, giving these images a screensaver-like ambience with indefinite duration. While some apps create this tranquil atmosphere through live action footage and others through animation, the goal is the same: to conjure an uninhabited world of natural beauty that is right at the user’s fingertips to discover.

If the target demographic for meditation apps is harried white-collar workers moving through the city, their interfaces directly contrast this urban lifestyle with natural imagery: lurid sunsets, dense forests, waves crashing on the shore (Brewer 2021). Magnus Atom, one of the animators who worked on the 2021 Netflix series The Headspace Guide to Meditation, explains, “There’s something inherently calming about natural imagery. When you pay attention to the cycles of nature—the life, death, and changing patterns—you can find metaphors for almost anything in life, both externally and internally. Perhaps that’s the Eastern philosophy in me talking.” In addition to their promise of universality via “Eastern” mysticism, these environmental visualizations, which are devoid of people, have a prelapsarian, untouched quality to them. Despite the numerous technical deliberations that went into their design, they invite the user to reimagine their relationship with their smartphone as somehow unmediated.

One of Headspace’s many short animations is called “Remember the Blue Sky.” The cartoon narrative shows a happy hiker out for a walk, enjoying the nice weather and clear sky until rainclouds appear, forcing them to flee from an incoming storm. The blue sky, as Puddicombe’s voice tells us, “is a perfect metaphor for the mind—a blank canvas on which thoughts, feelings, and experiences appear.” Comparing storm clouds to unwanted or intrusive thoughts, Puddicombe reminds us that the blue sky is “still there, without fail,” and that “it’s easy to forget that what we’re looking for is already here.” With both guided meditations, the thought defusion exercises used in DBT have been reimagined for the mythos of the digital cloud.[5]As scholars writing on the topic of media and environment have shown, natural metaphors, particularly the cloud metaphor, romanticize digital networks as weightless, placeless, and ephemeral despite … Continue reading The solutions to our problems are not only already there in our minds—they’re also on our screens.

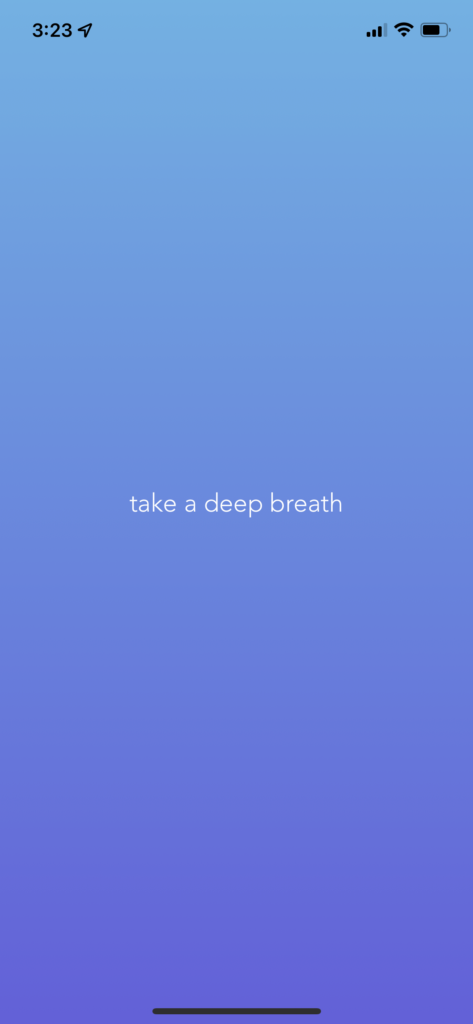

Similarly, when opening the Calm app, the first thing the user sees is a solid blue background with nothing but the words “take a deep breath.” The screen then shifts to an outdoor scene: Snow-topped mountains soar above a coniferous forest, at the foot of which is an alpine lake. The lake’s surface ripples slowly, almost imperceptibly, the quiet sounds of water rushing and birdsong emanating from nowhere. Superimposed over this pastoral tableau are the words “Find your Calm” (see figure 6a-b). These landscapes are empty, with not a human in sight, and their natural beauty has a vague sense of placelessness. In this digital utopia, inequality and difference don’t exist, and what is not beautiful can be imagined away. To find one’s Calm is to explore a natural milieu that is the sovereign user’s alone to inhabit, a directive that is only made stronger by the app’s repeated usage of the second person “you.” Calm’s ambient landscapes also evoke the so-called Instagram or wellness tourism that promotes far-flung places (particularly in the Global South) as “exotic playgrounds” for well-to-do travelers from the Global North by omitting visual signifiers of urban development (Putcha 2020, 450). Popularized by self-help memoirs like Eat, Pray, Love (2006) and ridiculed on the HBO limited series The White Lotus (2021– ), what wellness tourism sells is a process of self-discovery for the white and affluent. By immersing themselves in the beauty of a strange and mystical new land, they can then be transformed by an encounter with otherness (see hooks 2015). In their claim to universality, mindfulness apps cement whiteness as the invisible—but still quite audible—default.

It makes sense that meditation app creators go out of their way to avoid any human representation that might risk destroying this postracial fantasy (with the exception of celebrity cameos). When human-like characters are represented in an app’s design, like with Headspace’s, their rendering avoids markers of race, gender, and even age. Headspace’s drawn figures, with their simplified facial features, exaggerated proportions, and impossible skin colors in shades like blue and pink, look more like cartoon extraterrestrials than humans (see figure 7). Like the puppet characters on popular children’s shows like Sesame Street, they refuse to be situated within existing racial hierarchies, constructing a colorblind world where everyone is on the same playing field.

By envisioning meditation as a universal remedy or treatment that speaks to a shared human condition, mindfulness apps obfuscate very real differences in a historically significant moment where even the ability to breathe is a privilege. Much like how labeling Covid-19 “the great equalizer” rang painfully false for those disproportionately affected by the pandemic (immunocompromised and lower-income people of color), digital mindfulness’s reliance on an effortless form of breathwork takes on a kind of willful naïveté in the wake of George Floyd’s last words and images of patients hooked up to respirators. The breathwork of guided meditations is regular and serene, not ragged or shallow. With the meditation coach’s voice as the anchor, it invites the user to relinquish pain and suffering with every exhale.

Conclusion

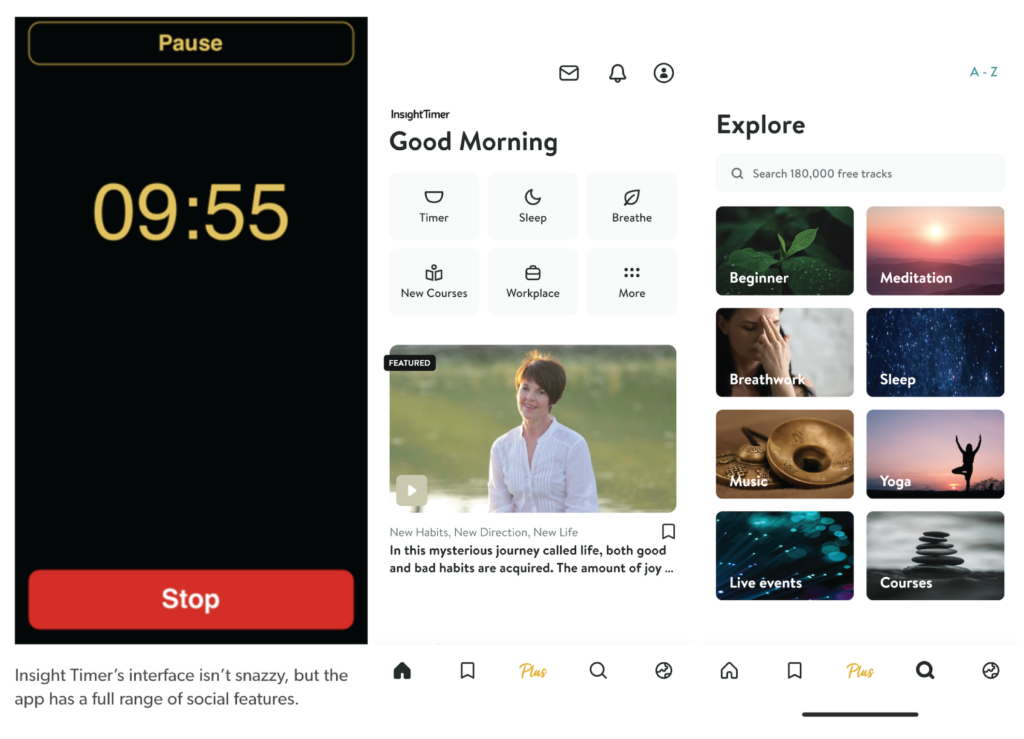

Has mindfulness, like the increasingly vacuous concepts of wellness and self-care, lost its meaning altogether? Here, we might look to a few apps that differentiate themselves from those I’ve discussed thus far in their refusal to accept the now ubiquitous and wholly commodified concept of “self-care.” Insight Timer is a free meditation app—one of the oldest, founded in 2009—that in its earliest iteration was simply a clock display accompanied by a gong sound to indicate the beginning and end of the meditation, emulating the experience of an in-person Buddhist meditation (see figure 8). As my Buddhist colleagues tell me, Insight Timer was once much more explicit about mindfulness’s Buddhist roots and functioned primarily as a social network to meet other Buddhists in their community.[6]This paragraph is inspired by the chapter titled “Searching for Digital Wellness” in Technoskepticism: Between Possibility and Refusal, a book in progress authored collectively by the DISCO … Continue reading The app would indicate how many people were “meditating with” you and give you the option of connecting with them outside the platform. In recent years, however, Insight Timer has come to increasingly resemble Calm and Headspace as its graphics and features have become sleeker, more colorful, and focused more on self-optimization than community. For example, users can track their “run streaks” and personal stats, which are prominently displayed on their feeds (see figure 8). Accordingly, Insight Timer has also become less overtly Buddhist, diluting religious specificity into the decontextualized “Eastern philosophy” that fuels wellness capitalism. Yet, it’s still worth remembering that Insight Timer once emphasized togetherness and community rather than self-regulation—that alternatives are indeed possible.

Likewise, apps like Shine, Liberate, and Exhale, which I touched on earlier, break with the Calm/Headspace model not simply because they feature primarily meditation instructors of color, but in their engagement with the process of meditation itself. While it’s true that these app don’t look all that aesthetically different from Calm and Headspace, nor do they make mindfulness’s Buddhist roots explicit, neither do they obscure racial and economic difference beneath a faux-Asian veneer. Instead, their guided meditations, such as Shine’s 2020 “Cope with Your Election Anxiety,” highlight how difficult emotions are very much intertwined with social inequalities, particularly for those with marginalized identities. (Compare this to Headspace’s “Politics Pack,” a curated list of the platform’s existing meditations prefaced by the caveat: “None of the exercises are explicitly political, but they are intended to help you breath, de-stress, and reset” [Headspace n.d.].)

Though Shine has since been acquired by Headspace Health, it still points to a different set of possibilities for how mindfulness apps can approach wellness differently. Meanwhile, Exhale, founded in 2021, is designed specifically for women of color to help them navigate their daily experiences of systemic racism. Its interface is striking. Rather than Calm’s Benetton-like roster of celebrities, Exhale prominently features close-ups of immaculately lit darker skin, which has historically been more difficult to light with photographic technologies that have been calibrated for whiteness (see figure 9). Guided meditations have titles like “Ancestors” and feature thumbnails of groups of women standing together, emphasizing togetherness rather than self-sufficiency (see figure 10). The app is also free, with additional features available for $4.99 a month, a fraction of the price of Headspace or Calm.

Rather than constructing an escapist fantasy that denies the existence of lived inequalities and power structures, which are then encoded within the interface, apps like Shine push us to reconsider how mindfulness is a way of surviving and being in—rather than fleeing from—the world. What if this approach to self-care was not focused exclusively on cure or reaching an unattainable ideal of “health,” but instead on survival and endurance? (Kim and Shalk 2021) In calling out the differences, rather than similarities, of our lived experiences, an interface that emphasizes how the existing system makes it impossible for everyone to be “well” on equal terms might paradoxically bring us closer together. It would slowly but surely chip away at the cult of the self the wellness industry has worked so hard to build, replacing it with something truly mindful.

Acknowledgements

I want to thank Neta Alexander and Lisa Nakamura for helping me develop this piece. Thanks also to my colleagues and friends at the DISCO Network who have pushed me to think more deeply about wellness, race, and disability in ways I never would have on my own.

Recommended Readings

Hu, Tung-Hui. 2022. Digital Lethargy: Dispatches from an Age of Disconnection. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Kim, Jina B., and Sam Shalk. 2021. “Reclaiming the Radical Politics of Self-Care: A Crip-of-Color Critique.” South Atlantic Quarterly 120 (2): 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8916074.

Mulvin, Dylan. 2018. “Media Prophylaxis: Night Modes and the Politics of Preventing Harm.” Information & Culture 53 (2): 175–202. https://doi.org/10.7560/IC53203.

Nopper, Tamara K., and Eve Zelickson. 2023. Wellness Capitalism: Employee Health, The Benefits Maze, and Worker Control. New York: Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/library/wellness-capitalism-employee-health-the-benefits-maze-and-worker-control/.

Williams, R. John. 2014. The Buddha in the Machine: Art, Technology, and the Meeting of East and West. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Zeavin, Hannah. 2021. The Distance Cure: A History of Teletherapy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

References

Ake, Catherine. 2022. “Headspace Users Tend to Come from Higher Asset Households.” The Harris Poll, March 11, 2022. https://theharrispoll.com/briefs/headspace-users-tend-to-come-from-higher-asset-households/.

Alexander, Neta. 2023. “Rest as Resistance? Theorizing Horizontal Media.” Presentation at the Society of Cinema and Media Studies, Denver, CO, April 12–15, 2023.

Amazon. 2021. “From Body Mechanics to Mindfulness, Amazon Launches Employee-Designed Health and Safety Program called WorkingWell Across U.S. Operations.” Amazon, May 17, 2021. https://press.aboutamazon.com/2021/5/from-body-mechanics-to-mindfulness-amazon-launches-employee-designed-health-and-safety-program-called-workingwell-across-u-s-operations.

Barclay, Elizabeth. 2017. “Meditation is Thriving under Trump. A Former Monk Explains Why.” Vox, June 19, 2017. https://www.vox.com/science-and-health/2017/6/19/15672864/headspace-puddicombe-trump.

Benjamin, Ruha. 2019. Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. London: Polity.

Bhuiyan, Nishat, Megan Puzia, Chad Stecher, and Jennifer Huberty. 2021. “Associations Between Rural or Urban Status, Health Outcomes and Behaviors, and COVID-19 Perceptions Among Meditation App Users: Longitudinal Survey Study.” JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 9 (5): e26037. https://doi.org/10.2196/26037.

Brewer, Jenny. 2021. “And Breeaaathe: The Animation Supergroup Creating Meditation TV for Netflix’s Headspace.” It’s Nice That, February 15, 2021. https://www.itsnicethat.com/features/headspace-guide-to-meditation-netflix-animation-150221.

Carruth, Allison. 2014. “The Digital Cloud and the Micropolitics of Energy.” Public Culture 26, no. 2 (Spring): 339–364. https://doi.org/10.1215/08992363-2392093.

Chapple, Craig. 2020. “Downloads of Top English-Language Mental Wellness Apps Surged by 2 Million in April Amid COVID-19 Pandemic.” Sensor Tower (blog), May 2020. https://sensortower.com/blog/top-mental-wellness-apps-april-2020-downloads.

Dyer, Richard. 1997. White: Essays on Race and Culture. London: Routledge.

Eidsheim, Nina. 2018. The Race of Sound: Listening, Timbre, and Vocality in African American Music. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Glover, Julian. 2021. “Who Gets to be the ‘Voice in Your Head?’ Meditation Apps Push to Diversify Offerings.” ABC7 Bay Area News, May 19, 2021. https://abc7news.com/mindfulness-meditationappsdiversity-new-voices-shine-app/10656934/.

Guest, Jennifer. 2019. The CBT Art Workbook for Coping with Anxiety. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Gunatillake, Rohan. 2012. “Generation Wise: How 21st-Century Buddhist Practitioners Are Changing Their Worlds and How They Are Going to Change Yours.” Keynote speech at FutureEverything, Manchester, UK, May 16, 2012. https://rohangunatillake.com/blog/generation-wise-my-future-everything-keynote/.

———. 2017. Modern Mindfulness: How to Be More Relaxed, Focused, and Kind While Living in a Fast, Digital, Always-On World. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

Gunter, Jen. 2018. “Worshipping the False Idols of Wellness.” New York Times, August 1, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/01/style/wellness-industrial-complex.html.

Headspace. N.d. “Approaching Politics: Calm Your Mind, then Take on the World.” Headspace. https://www.headspace.com/articles/approaching-politics-calm-your-mind-then-take-on-the-world.

Hess, Amanda. 2019. “The App That Tucks Me in at Night.” New York Times, July 17, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/07/17/arts/calm-app-sleep-meditation.html.

hooks, bell. 2015. “Eating the Other.” In Black Looks: Race and Representation. 2nd ed., 21-40. New York: Routledge.

Hu, Tung-Hui. 2015. A Prehistory of the Cloud. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

———. 2022. Digital Lethargy: Dispatches from an Age of Disconnection. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Kim, Jina B., and Sam Shalk. 2021. “Reclaiming the Radical Politics of Self-Care: A Crip-of-Color Critique.” South Atlantic Quarterly 120 (2): 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1215/00382876-8916074.

Jablonsky, Rebecca. 2022. “Meditation Apps and the Promise of Attention by Design.” Science, Technology, & Human Values 47 (2): 314–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/01622439211049276.

Laderer, Ashley. 2019. “The Voice That Puts You in the Zone.” Elemental, July 26, 2019. https://elemental.medium.com/what-makes-a-voice-soothing-fc0e9fd5e624.

Lowrey, Annie. 2021. “The App That Monetized Doing Nothing.” The Atlantic, June 4, 2021. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2021/06/do-meditation-apps-work/619046/.

May, Andrew D., and Elana Maurin. 2021. “Calm: A Review of the Mindful Meditation App for Use in Clinical Practice.” Families, Systems, & Health 39 (2): 398–400. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000621.

McKay, Matthew, Jeffrey C. Wood, and Jeffrey Brantley. 2007. The Dialectical Behavioral Therapy Skills Workshop: Practical DBT Exercises for Learning Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotion Regulation & Distress Tolerance. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Workshop: Practical DBT Exercises for Learning Mindfulness, Interpersonal Effectiveness, Emotion Regulation & Distress Tolerance. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications, Inc.

Mulvin, Dylan. 2018. “Media Prophylaxis: Night Modes and the Politics of Preventing Harm.” Information & Culture 53 (2): 175–202. https://doi.org/10.7560/IC53203.

Nopper, Tamara K., and Eve Zelickson. 2023. Wellness Capitalism: Employee Health, The Benefits Maze, and Worker Control. New York: Data & Society Research Institute. https://datasociety.net/library/wellness-capitalism-employee-health-the-benefits-maze-and-worker-control/.

Peters, John Durham. 2015. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Peterson, Jake. 2020. “Ease Your Coronavirus Worries With These Meditation Apps.” Gadget Hacks (blog), March 19, 2020. https://smartphones.gadgethacks.com/news/ease-your-coronavirus-worries-with-these-meditation-apps-0277048/.

Putcha, Rumya S. 2020. “After Eat, Pray, Love: Tourism, Orientalism, and Cartographies of Salvation.” Tourist Studies 20 (4): 450–466. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468797620946808.

Shestack, Miriam. 2022. “What’s the Matter with Workplace Wellness?” OnLabor, May 30, 2022. https://onlabor.org/whats-the-matter-with-workplace-wellness/.

Slunecko, Thomas, and Laisha Chlouba. 2021. “Meditation in the Age of its Technological Mimicry: A Dispositive Analysis of Mindfulness Applications.” International Review of Theoretical Psychologies 1 (1): 63–77. https://doi.org/10.7146/irtp.v1i1.127079.

Stoever, Jennifer Lynn. 2016. The Sonic Color Line: Race and the Cultural Politics of Listening. New York: NYU Press.

Strings, Sabrina. 2019. Fearing the Black Body: The Racial Origins of Fat Phobia. New York: NYU Press.

Turner, Fred. 2006. From Counterculture to Cyberculture: Stewart Brand, the Whole Earth Network, and the Rise of Digital Utopianism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ward, Madeline. 2023. “Why We Need to Stop Labeling Behaviors Influencing a Person’s Weight Ideal or Healthy.” AMA Journal of Ethics 25 (7): 472–477. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2023.472.

Williams, R. John. 2014. The Buddha in the Machine: Art, Technology, and the Meeting of East and West. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Zeavin, Hannah. 2021. The Distance Cure: A History of Teletherapy. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2001. “From Western Marxism to Western Buddhism.” Cabinet, no.2. https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/2/zizek.php.

Zuckerbrod, Julie. 2022. “Workplace Wellness Programs Have Overlooked Health Equity.” Say Ahhh! (blog), Center for Children and Families, McCourt School of Public Policy, Georgetown University, February 11, 2022. https://ccf.georgetown.edu/2021/02/22/workplace-wellness-programs-have-overlooked-health-equity/.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Incidentally, though recent lawsuits have been filed stating that workplace wellness initiatives violate the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), weight is not a legally protected category, and obesity is not considered a disability under ADA (see Shestack 2022). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | In April 2020, 3.9 million new users installed Calm on their phones, with Headspace coming in second with 1.5 million installs (see Chapple 2020). |

| ↑3 | As of 2019, Headspace had secured 75.2 million dollars and some stars are paid as much as $100k per recording session (Laderer 2019). |

| ↑4 | Slavoj Žižek makes a similar argument that global capitalism thrives on the reconciliation of the mythos of the “exotic” Far East with neoliberal ideology (Žižek 2001). |

| ↑5 | As scholars writing on the topic of media and environment have shown, natural metaphors, particularly the cloud metaphor, romanticize digital networks as weightless, placeless, and ephemeral despite their very real physical presence and immense carbon footprint (as in the numerous data centers demanded by cloud computing) (see Hu 2015; Peters 2015; and Caruth 2014). |

| ↑6 | This paragraph is inspired by the chapter titled “Searching for Digital Wellness” in Technoskepticism: Between Possibility and Refusal, a book in progress authored collectively by the DISCO Network. |