Biomedical Surveillance in the Child Welfare System

Biomedical Surveillance in the Child Welfare System

As artificial intelligence quietly shapes the child welfare system, families of color remain the primary targets of intervention. At least twenty-six jurisdictions, including the City of New York (NYC), have considered or used AI-driven tools to make decisions for child protection.[1]Anjana Samant et al., Family Surveillance by Algorithm: The Rapidly Spreading Tools Few Have Heard Of (ACLU, September 29, 2021), https://www.aclu.org/documents/family-surveillance-algorithm; Nikki … Continue reading These tools operate in a racially skewed context, relying on data often collected without meaningful consent. Like the criminal legal system,[2]Christopher R. Adamson, “Punishment After Slavery: Southern State Penal Systems, 1865–1890,” Social Problems 30, no. 5 (June 1983): 555–69, https://doi.org/10.2307/800272; Julia Angwin et … Continue reading the American racial caste structure underpins the child welfare system.[3]Gwendoline M. Alphonso, “Political-Economic Roots of Coercion: Slavery, Neoliberalism, and the Racial Family Policy Logic of Child and Social Welfare,” Columbia Journal of Race and Law 11, no. 3 … Continue reading In New York City, nearly half of Black children will be investigated by age eighteen, and Black children are six times more likely to be investigated than white children.[4]Frank Edwards et al., “Contact with Child Protective Services Is Pervasive but Unequally Distributed by Race and Ethnicity in Large US Counties,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences … Continue reading It is within this racialized context and broader regime of racialized surveillance that predictive algorithms are programmed, trained, and deployed.[5]Charlotte Baughman et al., “The Surveillance Tentacles of the Child Welfare System,” Columbia Journal of Race and Law 11, no. 3 (2021): 501–32, https://doi.org/10.52214/cjrl.v11i3.8743; … Continue reading

The NYC Administration for Children’s Services (ACS) has a history of racial harm targeting Black families.[6]Antwuan Wallace et al., Administration for Children’s Services Racial Equity Participatory Action Research & System Audit: Findings and Opportunities (National Innovation Services, 2020), … Continue reading Parents describe child welfare as “an unavoidable system,”[7]Rise Participatory Action Research (PAR) Team et al., An Unavoidable System; The Harms of Family Policing and Parents’ Vision for Investing in Community Care (Rise / TakeRoot Justice, 2021), 6, … Continue reading one where poverty, identity, and life crises are pipelines to punitive and carceral interventions.[8]Eli Hager, “Police Need Warrants to Search Homes. Child Welfare Agents Almost Never Get One,” ProPublica, October 13, 2022, … Continue reading Investigations can lead to child removal or termination of parental rights, outcomes that disparately impact Black families.[9]Christopher Wildeman, Frank R. Edwards, and Sara Wakefield, “The Cumulative Prevalence of Termination of Parental Rights for US Children, 2000–2016,” Child Maltreatment 25, no. 1 (2020): … Continue reading Emerging research suggests that algorithms have not increased disparities for Black children.[10]Martin Eiermann, “Algorithmic Risk Scoring and Welfare State Contact among US Children,” Sociological Science 11 (2024): 707–42, https://doi.org/10.15195/v11.a26. However, algorithms are shaped by coercive and racialized practices, and claims of fairness obscure how they operationalize and legitimize the state’s power. Through a veneer of objectivity, these tools transform constructed racial disparities into seemingly immovable realities that regulate families and normalize racialized surveillance.[11]Simone Browne, Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness (Duke University Press, 2015); Copeland, “Dismantling the Carceral Ecosystem.”

My research shows how NYC quietly deploys algorithms together with longstanding practices of coercive health data collection to establish a tech-enabled biomedical surveillance apparatus ostensibly for child protection. Through thirty-six in-depth interviews with thirteen Black parents and pouring over 1,300 pages of public records, I outline how this system transforms child protection investigations into algorithmic family surveillance, creating implications not only for current cases but also future ones. The system’s quiet operation makes this process even more alarming as families are unaware that their most intimate circumstances are being converted by machine learning into risk scores.

Algorithms in NYC Child Welfare

In 2017, ACS began using the “service termination conference” model, (renamed to the “repeat maltreatment model”) to assess and monitor families in preventive services.[12]Jeff Thamkittikasem, Implementing Executive Order 50 (2019): Summary of Agency Compliance Reporting (NYC Algorithms Management and Policy Officer, 2020), … Continue reading Subsequently, in 2018, another model was launched to identify cases at highest risk for severe harm. Following the tragic deaths of two children,[13]J. Khadijah Abdurahman, Calculating the Souls of Black Folk: Predictive Analytics in the New York City Administration for Children’s Services,” Columbia Journal of Race and Law Forum 11, no. 4 … Continue reading ACS developed both models in-house with assistance from academic consultants at New York University and the City University of New York.[14]Brian Clapier, “Building Capacity to Use Predictive Analytic Modeling in Child Welfare,” letter, May 13, 2016, … Continue reading The algorithms include over 260 data points about parents, children, and their families, including demographic information, service history, and even details related to mental health.[15]Division of Policy Planning and Measurement Predictive Analytics (DPPM), Technical Document: Service Termination Conference (STC) (ACS–Office of Research Analytics, 2022), … Continue reading ACS trained both models on cases from 2009 to 2017 using predictive analytics. Based on this historical data, these predictive risk models identify patterns in case outcomes and apply them to incoming cases, attempting to predict the likelihood that a child will experience future harm.

ACS uses the risk scores to determine how closely families are monitored during investigations and to classify them as “high risk” or “low risk” when assessing their readiness to exit preventive services.[16]NYC Office of Technology & Innovation, “Summary of Agency Compliance Reporting of Algorithmic Tools,” 2023, updated March 2024, … Continue reading The predictions also allow ACS to evaluate its contracted service providers by comparing families’ risk scores or “service needs” to providers’ performance outcomes.[17]New York City Administration for Children’s Services, FY2023 Prevention Services Scorecard Methodology (New York City Administration for Children’s Services, 2022), … Continue reading Though framed as efficient and protective measures, especially amid 60,000 investigations annually,[18]ACS, Demographics. these algorithms rely on aggressive data collection practices that undermine families’ rights. Because this information is often gathered under coercive conditions, the resulting data is at risk of being faulty and failing to represent families accurately.

The Path from Investigation to Algorithmic Surveillance

Child welfare investigations often begin with adversarial and traumatic encounters.[19]Hager, “Police Need Warrants”; Parent Legislative Action Network (PLAN) Coalition, Family Court Justice: Miranda Rights for Families (NYU Wagner / Bronx Defenders, October 2021), … Continue reading They may be prompted by a personal crisis.[20]Kara R. Finck and Susanna Greenberg, “The Family Regulation System and Medical-Legal Partnerships,” Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics 51, no. 4 (2023): 831–37, … Continue reading Parents I interviewed experienced a wide range of conditions, including domestic violence and signs of postpartum depression, that led them to scrutiny. Unbeknownst to them, their attempts to seek help became child maltreatment concerns, which were reported to the state child abuse hotline. Racism, sexism, and homophobia also animate reports of child maltreatment. One parent was reported by a trusted therapist who interpreted and embellished the mother’s polyamorous relationship as a cause for concern. ACS is required by law to investigate reports that come to their attention. This process unfolds under the threat of family separation, coercing parents into disclosures and compliance. During investigations, caseworkers gather information about families’ finances, family history, housing, mental health, and medical history, inputs that are later used to generate algorithmic risk scores. Only two parents out of the thirteen I interviewed knew about ACS’s algorithms. Kassy was unaware until our interview.[21]“Kassy” (pseudonym), interview by Ashleigh Washington, virtual, July 2024. She said, “They’re able to do that within their database because they know how to make a human feel inhumane, you know.” Here, inhumane signaled how dehumanized she felt—reduced to a number for the algorithm. Her story illustrates how help-seeking became a pathway into algorithmic surveillance.

A twenty-five-year-old college student and first-time mother, Kassy and her child were thrust into the child welfare system in 2023. Just three months postpartum, she walked into a police precinct with her infant son to report that she had been assaulted by her child’s father. Instead of safety, she was met with suspicion. “[The officer] basically said, I’m recording, you know, just in case you try to change the story or something. And I’m like, what?” Kassy was treated as not a survivor but a suspect, a judgment that would follow her. Hours later, in the middle of the night, Kassy was awakened by someone knocking on her door “like the police,” marking her first encounter with ACS. The police officer had reported Kassy’s disclosure to the state child abuse hotline, a biased and legally contested practice that treats domestic violence as automatic evidence of parental neglect, triggering an investigation.[22]Nicholson v. Scoppetta, 3 N.Y.3d 357 (N.Y. Ct. App. 2004), https://www.nycourts.gov/LegacyPDFS/IP/cwcip/Training_Materials/FP_Training/Nicholson_V_Scoppetta-3N.Y.3D357.pdf; Molly Schwartz, “Do We … Continue reading Kassy described the experience as terrifying and deeply violating.

I heard my doorbell ringing. I’m scared. You know, my child’s father just put his hands on me. It’s late at night and someone is ringing my doorbell. They were like, “It’s ACS. Open up the door.”

The late-night demand, delivered with an unfamiliar acronym and insistence on entry, echoed the police, producing fear and intimidation rather than safety.

When I opened the door they came inside of my apartment, and they were automatically like, “Take off his clothes.” I’m like, “What?” So, I had to wake my son up, take his clothes off. I made a report stating that my child’s father put his hands on me, there’s nothing wrong with the child. Why are you telling me to take off his Pampers?

Caseworkers routinely ask parents to undress their children and inspect personal belongings, offering little explanation. Kassy tearfully described the moral and psychological injury of exposing her son’s genitals to strangers only hours after she had been violated by her partner and the police.

I felt like I was doing something wrong. I felt like I was being judged by everybody. It takes a psychological effect, when someone just comes in your house and does that. Because people have to remember, your child is also a part of you . . . they told me to take off my child’s pants. And that’s like saying take off my pants. So… shit really broke me for months, you get what I’m saying? It was very inhumane. I cried for a month straight after that first visit. It was like, is this reality right now? Like, am I a criminal?

ACS’s intimidation resembled practices of the police state. The commands, strip searches of children, and coercing families to submit to practices that violated their autonomy and rights were defining aspects of parents’ experiences. Amid fear and confusion, parents often allowed caseworkers into their homes and answered questions, unaware of their right to decline and seek legal counsel. Parents engaged with ACS unaware their words and actions could affect the investigation’s outcome and algorithmic assessment. In every interview, parents discussed the power of medical consent and how it was extracted from them. They emphasized not just what happened but how it made them feel.

The Illusion of Consent and Privacy

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) is widely understood to protect medical privacy.[23]Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996, Pub. L. No. 104-191, 110 Stat. 1936 (1996),chttps://www.congress.gov/bill/104th-congress/house-bill/3103/text. Yet within the child welfare system, these protections become a source of power over families. At the start of an investigation, and often under pressure, parents are asked to provide access to their personal health information by signing HIPAA forms. These forms permit caseworkers to communicate directly with parents’ and children’s healthcare providers to gather information. Parents described signing the documents without understanding the scope or purpose and at times under duress—in an emergency room after their child’s fall or from a hospital bed after giving birth, for example. The resulting health data feed ACS’s risk assessments, transforming coercive consent into algorithmic form. With this permission granted, ACS may contact doctors, pediatricians, mental health providers, or substance-use programs to collect records on diagnoses, medications, and therapy. When another parent, Kaye, revoked her consent, her provider continued to share information with ACS anyway.[24]“Kaye” (pseudonym), interview by Ashleigh Washington, virtual, May 2024. Another parent, Emiras, described being “blackballed” after refusing to sign HIPAA forms while her children were temporarily placed in foster care: “They got mad ’cause I refused to sign. So, then they lied [to the judge] and stopped my visits with my children.”[25]“Emiras” (pseudonym), interview by Ashleigh Washington, virtual, March 2024.

Some parents hoped signing the release would simply reduce the intrusion and intensity of their case. Returning to Kassy’s experience, during subsequent visits, the caseworker explained that they were not concerned about her but her partner’s actions. Yet Kassy continued to live under surveillance. She described signing a medical release for her child:

They were basically just telling me . . . “Here’s the HIPAA statement. We just wanted to sit down with you to see if…he’s up to date with his medical and if he’s gotten his shots.” They just mainly kind of read it quickly to me . . . and then they made me sign the papers at the time. I didn’t really look closely into it, because I just wanted them out of my face and out of my life, so I just wanted to sign it off.

ACS continued visiting her home, asking questions, and collecting information without investigating the father. “I got stuck with it! They came and investigated like me and my son were the abuser.” Over the sixty-day investigation phase, families endure repeated home visits, case conferences, and mounting expectations to prove their adequacy. Furthermore, parents are frequently routed into counseling interventions like functional family therapy or child-parent psychotherapy. Though they are labeled voluntary, parents who decline face the possibility of court intervention. Kaye explained that, within days of her investigation, ACS gave her three options: “preventive services, preventive services with court supervision, or removal of the child.” She accepted preventive services to avoid potentially losing her child.

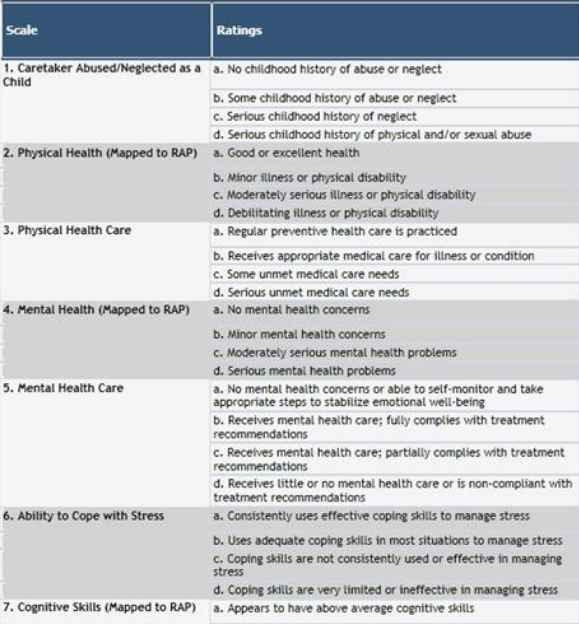

Throughout the services, caseworkers conduct a Family Assessment and Service Plan (FASP), including an inventory of health and mental health questions (see figure 1) using self-reported information, observations, drug tests, and medical documentation to assess coping, mental health and cognitive ability.[26]New York State Office of Children and Family Services, Family Assessment and Service Plan (FASP) Guide (New York State Office of Children and Family Services, 2017, https://perma.cc/P9EA-4WZP. This assessment is central to the algorithm’s predictions; at least seventy FASP data points are used to make predictions in the Repeat Maltreatment model. The model also captures the number of enrollments a family had in therapy-focused preventive interventions, accounting for at least twenty-one data points.[27]DPPM, Service Termination Conference (STC). These interventions ranged from three to twelve months of intensive contact and ongoing assessment that parents experienced as soft surveillance.[28]Linda M. Callejas, Lakshmi Jayaram, and Anna Davidson Abella, “I Would Never Want to Live That Again,” Child Welfare 99, no. 4 (2021): 27–50, https://www.jstor.org/stable/48647841; Darcey H. … Continue reading Furthermore, none of the parents I interviewed knew that their information—over 260 data points of investigation history, demographic information, health, and other data—was used to calculate an AI-enabled risk score of their child’s future safety.

Like Kaye, Kassy’s case was unfounded for maltreatment, but she was still referred to ACS’s preventive services. Kassy accepted, hoping to meet other new moms, but the experience felt more like being studied in a “social experiment” than support. During a session, she noticed a woman observing her son and other children in one room, and when Kassy shared about her experience as a Black mother, the group facilitator became upset, suggesting that race was irrelevant to the discussion. Kassy later noticed a sign on the door that read: “Children’s Evaluation and Rehabilitation Center.” She left the group infuriated and never returned.

The program tried to make it seem like I was crazy for speaking out. I even told them, “Y’all have me signing papers that I didn’t even see what I was signing. Can you guys email me a copy of what I signed?” I still haven’t even received a copy of it. So, they violated so many rights! . . . They violated me and my son.

When she informed her caseworker that she no longer wanted to participate in the services, they pushed back and suggested that they were concerned about her well-being. She feared her disengagement would trigger more allegations, but her preventive case was closed shortly after she advocated for herself and threatened that she’d seek an attorney.

While a few parents found aspects of the counseling helpful, the support came with constraints on their employment, time, and psychological stability. When asked about the services offered through ACS, Kassy said, “They made my life a living hell! Literally, there was nothing that they have done that was beneficial to me or my son . . . while going through postpartum depression and domestic violence.” Living under the oversight of child protection undermines parents’ agency and humanity.[29]Callejas, Jayaram, and Abella, “I Would Never Want to Live That Again”; Kelley Fong, “Getting Eyes in the Home: Child Protective Services Investigations and State Surveillance of Family … Continue reading Parental agitation, missing a home visit, or frustration with the process could be interpreted and documented as signs of mental illness and therefore inadequate, “risky” parenting. Kassy described the surveillance and contradictions of preventive services: “You know, they were trying to catch me slipping with something, and they didn’t find anything. They didn’t care about me getting abused. They just wanted to take the child. That’s what they wanted to do.”

For Kassy, child-maltreatment risk assessment was not neutral. It was a systemic, racialized, and gendered algorithm—one intended to punish and discipline mothers like her. She said, “I’m a Black single mother living in the Bronx, right? I’m in a domestic violence relationship. There’s already not a lot of resources in the Bronx as it is. They don’t care about the environment out there in the Bronx, you get what I’m saying? These people are coming into your lives. They’re trying to make it seem like you’re a bad mom. They’re watching every move that you do.”

Child Welfare’s Invisible Biomedical Surveillance Apparatus

In NYC’s child welfare system, predictive analytics operate within an expansive ecosystem in which intervention is framed as support for families, but in practice functions to sort, judge, and monitor them. This algorithmic ecosystem comprising systemic racism, poverty, and misogyny alongside the authority of mandated reporting policies, healthcare providers, nonprofits, evidence-based mental health models, and extractive data collection practices upholds institutional power through algorithmically guided care that coerces participation and compliance. As Kassy reflected, “Maybe if they would have gotten the families the resources they needed, they wouldn’t need that technology.”

Investigations are not just a pathway to services; they are a gateway into algorithms. Once inside, families are funneled through therapy interventions framed as voluntary but enforced through threat of court involvement. These programs become data-producing mechanisms that feed and sustain predictive models. Participation is tracked, personal information is mined, and compliance becomes a proxy for child safety. This demonstrates a tech-enabled biomedical surveillance apparatus in child welfare: a system where medical, psychological, and behavioral data are extracted without meaningful consent, interpreted, and used to justify intervention. As J. Khadijah Abdurahman powerfully writes, NYC’s algorithms “calculate the souls” of Black families.[30]Abdurahman, “Calculating.” This captures precisely what my research shows—that algorithmic practices extend racialized surveillance under the guise of care, transforming families’ most intimate data into tools of control.

Footnotes