The Power of Racialized Emotions: Racial Profiling and Surveillance within the Platform Economy

The Power of Racialized Emotions: Racial Profiling and Surveillance within the Platform Economy

On April 1, 2022, a white female Uber passenger, Jill Berquist, was arrested in Minneapolis and later charged for one count of misdemeanor disorderly conduct after assaulting a Black male Uber driver, Wesley Gakuo.[1]Paul Walsh, “Minneapolis Woman Charged after 2022 Racist Tirade against Black Uber Driver Captured on Video,” Minnesota Star Tribune, July 12, 2023, … Continue reading A recording of the incident went viral after it was uploaded on YouTube.[2]Naasir Akailvi, “Woman Charged in Viral Video of Racist Rant Directed at Uber Driver,” KARE, July 12, 2023, … Continue reading In the video, Gakuo’s passengers called him a series of racial slurs, kicked his car, and called 911 to falsely claim that she was the one assaulted. What this incident, and others like it, remind us of is the persistent role structural racism plays in shaping interactions and digital infrastructures within the platform economy. Conflict stemming from racialized and gendered understandings of power, status, and privilege are not new social phenomena in the United States. Yet, platform work, such as ridesharing, is thought of as free of racial discrimination due to applications’ use of algorithmic management to assign tasks and allocate earnings. It’s time we reexamine the role that historical processes of racial inequality and domination play in shaping interpersonal interactions and digital infrastructures within the platform economy.

Power has always been structured by gendered and racialized systems of hierarchy, especially in the United States. However, platform applications have afforded customers the power to surveil workers, Black workers in particular, and to place on them the burden of emotional labor management, at the cost of their mental and physical comfort. After interviewing 44 Black platform gig workers across the United States, I found that the “burden of emotional management required of platform work, and the added stress of navigating racial profiling and surveillance increases the mental and emotional toll of platform work. Despite the high mental and emotional toll of platform work, wages from platform applications are not sustainable, causing most workers to have to rely on multiple gigs.”[3]Jaylexia Clark, “Racing Towards Global Racial Capitalism: Investigating the Impact of Racial and Gender Inequality on the Platform Economy” (PhD diss., University of Notre Dame, 2024), 51–55, … Continue reading Black platform workers’ insight into the platform economy reveal how platform applications can reproduce racial inequality and domination in two distinct ways: (1) Platform work reproduces disparities in the burden of emotional labor for Black platform workers, and (2) platform applications enforce the surveillance of workers without concern for the pre-existing structures of racial profiling, which places the burden of finding ways to safely “gig” or perform tasks onto workers.

How Black platform workers navigate structural racism within the platform economy can help us understand the new role platform applications play in reproducing racism and sexism by shifting the power to control work conditions, pay, and assignments from workers to customers. Platform application users, empowered by their rating systems, can assert racial-emotional dominance over platform workers via the apps’ infrastructure. In line with theories that suggest that individuals readily engage in conflict when situational odds are in their favor,[4]Randall Collins, “Conflict Theory and the Advance of Macro-historical Sociology,” in Frontiers of Social Theory: The New Syntheses, ed. George Ritzer (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), … Continue reading the very structure of the platform economy is heavily weighted in favor of clients over platform workers. What qualifies as professional or friendly behaviors is decided by the client, yet clients live in a racial capitalist society that has historically created different standards for Black workers. Rating workers is just one part of platform applications’ digital infrastructures that determine what tasks they will be assigned in the future. As each task has different payouts, this dynamic also affects workers’ income. By becoming aware of the role users play in facilitating this cycle of discriminatory outcomes within the platform economy, they can become better advocates. How consumers participate in an increasingly digital reality has broader implications for the future of racial inequality. As such, it is imperative that we understand and pay attention to the insights provided by the lived experiences of Black platform workers.

Feelings on Demand: Racialized Emotions and Labor

In his 2018 address to the American Sociological Association, Eduardo Bonilla-Silva urged “sociologists to take emotions seriously.”[5]Eduardo Bonilla-Silva, “Feeling Race: Theorizing the Racial Economy of Emotions,” American Sociological Review 84, no. 1 (2019): 2, https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122418816958. Hegemonic emotional domination plays a vital role in a racial economy wherein the feelings of dominant actors who operate with a belief and emotions about themselves as “good” are prioritized. In a racial capitalist society, the racialization of emotions helps sustain social systems and individual practices that reinforce racial and gender inequality.

In contrast to the traditional economy, wherein scholars describe emotional labor as “invisible,” companies like DoorDash, Instacart, and Uber give customers/clients the option to explicitly rate the degree to which workers performed emotional labor when fulfilling tasks. Customers do not simply “feel the power”; they actively participate in surveilling workers and are given digital space for reproducing emotional domination over workers. Through the social construction of racialized emotions, actors in a dominant group create a feeling or sense of self-worth separate from individuals racialized as “others.”[6]Bonilla-Silva, “Feeling Race,” 3. Those racialized as “other,” part of the nondominant group, are seen as individuals who should be feared and supervised.[7]Bonilla-Silva, “Feeling Race,” 3. In turn, these feelings of distrust and fear became a source of “feeling power.” The feeling power of hegemonic emotional domination has physical and emotional consequences for Black platform workers, yet this aspect is largely overlooked in research articles that discuss the platform economy. The perception that algorithmic management reduces bias within platform work as compared to traditional work makes invisible the very real ways in which customers’ emotions and expectations regarding the service provided to them, coerces workers to dress a certain way, accept specific tasks, and engage customers, restaurants, and residential structures with caution and weariness.

Additionally, the narrative perpetuated by major platform application companies that hail their apps as simply “providing a service” has worked to reinforce customers’ expectations that platform workers perform certain emotions and work within the confines of racial hegemonic emotional domination. These expectations are the most significant contributor to the “performance weariness” Black men and women experience when working within the on-demand side of the platform economy. This is made clear through interviews that center the experiences of Black platform workers who must navigate both racial profiling and customers’ emotions. Emotional labor is defined as “the display of expected emotions by service agents during service encounters.”[8]Blake E. Ashforth and Ronald H. Humphrey, “Emotional Labor in Service Roles: The Influence of Identity,” Academy of Management Review 18, no. 1 (1993): 88, https://doi.org/10.2307/258824. What is unique about emotional labor in the platform economy is that application companies equip customers with the power to reinforce emotional domination over workers. Failing to perform emotional labor can result in lower ratings, negative reviews, and fewer tips for Black platform workers. Despite the platform application companies’ assertion that algorithms used to manage platform work—assign tasks, calculate ratings—are bias-free, racialized emotions shape outcomes and work conditions of gig work. Platform application companies like Uber, DoorDash, and Instacart rely on customers to collect information on workers’ actions and behaviors to rank workers and assign new tasks through the application. The data collected from customers is far from neutral.

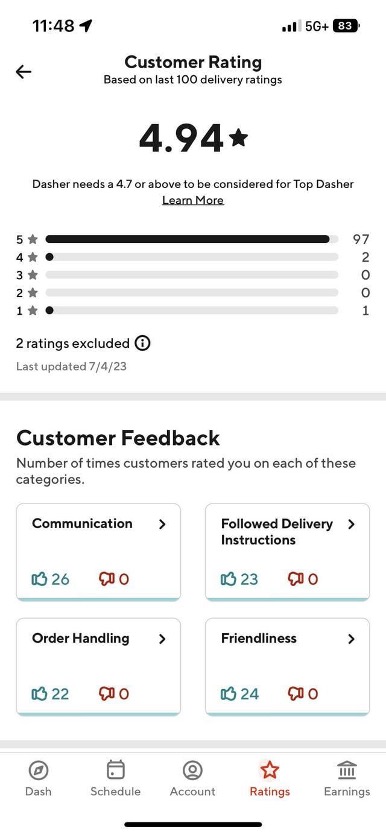

Customers’ preconceived stereotypes and beliefs shape their assessment of workers’ behavior. Take, for example, the data collected from customers regarding the level of “friendliness” performed by workers (see figure 1). By coding emotions that are inherently gendered and racialized, such as “friendliness,” customers are given a platform to police emotions and enact emotional domination. If a driver fails to comply with customers’ expectations surrounding the performance of emotional labor, it can result in lower rankings, fewer assigned tasks, and less earnings.

Tanya, a female Uber driver I interviewed, stated, “I get to be the thing that changes their thoughts on what a Black woman is by displaying kindness.” She understands that her facial reactions, tone of voice, and gestures are all perceived under a gendered and racialized lens.[9]Marlese Durr and Adia M. Harvey Wingfield, “Keep Your ‘N’ in Check: African American Women and the Interactive Effects of Etiquette and Emotional Labor,” Critical Sociology 37, no. 5 (2011): … Continue reading Tanya elaborates that when handling customers who explicitly express their inherent biases, she chooses to respond with the utmost kindness and generosity, because she refuses to validate clients’ racially biased preconceptions or risk losing tips, receiving a lower rank, or even a complaint on her profile. When Black female platform workers like Tanya say that they feel the need to smile in a friendly way and be overly accommodating to avoid scrutiny, negative ratings, and gendered criticism, it is because their emotional labor is made hypervisible via the codification of emotions through customer ratings.[10]Clark, “Racing Towards Global Racial Capitalism.”

During my interviews with Black platform workers, many expressed the need to manage their emotions to ensure customers’ comfort. At times, this meant prioritizing customers’ feelings and expectations over their own mental and emotional health. When picking up passengers, dropping off groceries to customers, or announcing and identifying themselves to justify why they are in a space, Black platform workers cannot stop performing emotional labor. Its hypervisibility is a built-in expectation.

Platform application companies have codified, streamlined, and capitalized on emotions. The racialization of emotions helps sustain social systems and individual practices that reinforce racial and gender inequality. Yes, emotions have been commodified and structured in the US work environment for decades now, “in an increasingly service-oriented economy, emotions have become yet another form of labor that workers must produce and sell in the capitalist marketplace.”[11]Adia Harvey Wingfield, “Are Some Emotions Marked ‘Whites Only’? Racialized Feeling Rules in Professional Workplaces,” Social Problems 57, no. 2 (2010): 252, … Continue reading When platform applications calculate workers’ performance ratings using scores from categories such as “friendliness,” they ignore the very extent to which our social world holds different standards for what performing “friendliness” looks like for Black men and women.[12]Wingfield, “Are Some Emotions Marked ‘Whites Only’?” In a gendered, racial capitalist system, Black men and women have to work twice as hard, smile more often, and engage in overly respectful tones to avoid being perceived as intimidating or threatening.

From Tears to Fears: Racial Profiling Platform Workers

The impact of hegemonic emotional domination goes beyond clients feeling upset because their Uber driver did not ask if they wanted water or did not engage in warm pleasantries. Emotions are not the only aspect of the work that is surveilled. Black platform workers’ entire bodies and set of behaviors are monitored from the moment they accept a task to its fulfillment. Racial profiling shapes the work conditions of Black platform workers regardless of gender. “Once a group is racialized as ‘savage’ or ‘dangerous,’ its members are feared and seen in need of supervision.”[13]Bonilla-Silva, “Feeling Race,” 3. Racial profiling can be defined as the emotional habitus or “set of anxious, affective” behaviors of surveillance that White individuals engage in based on a fear of Blackness and the belief that African Americans are inherently criminal.[14]Jacinta M. Gau and Kareem L. Jordan, “Profiling Trayvon: Young Black Males, Suspicion, and Surveillance,” in Deadly Injustice: Trayvon Martin, Race, and the Criminal Justice System, eds. Devon … Continue reading When entering grocery stores,[15]Shaun L. Gabbidon, “Racial Profiling by Store Clerks and Security Personnel in Retail Establishments: An Exploration of ‘Shopping while Black’,” Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 19, … Continue reading when driving, or even when walking on the sidewalk,[16]Kenneth Meeks, Driving While Black: Highways, Shopping Malls, Taxi Cabs, Sidewalks—How to Fight Back if You Are a Victim of Racial Profiling (Crown, 2000). Black Americans are surveilled simply while existing and performing daily tasks in US society. Working on platform applications is no exception.

In one interview, DoorDash driver John told me, “I don’t deliver to apartments. I don’t deliver to certain neighborhoods…I also don’t do deliveries at night.” When I asked why, he told me about a fellow Black male DoorDasher he knows who was harassed by police when making a delivery to an apartment complex after tenants “reported a Black man walking around.” The multiple layers of surveillance that Black platform workers operate under have their mental health costs, as customer surveillance coupled with racial profiling directly impacts work conditions in the platform economy. For Black workers operating within the on-demand side of the platform economy, racial profiling shapes which tasks they accept, as well as the strategy they employ when completing certain tasks. Racial profiling in an affluent or all-white neighborhood is a risk that is simply not worth taking for many drivers who prioritize their life over completing an additional task. Anderson, another DoorDash driver I interviewed, mentioned Amber Guyger, the former Dallas police officer who killed her unarmed Black neighbor after stepping into his apartment and mistaking it for her own. Anderson was not the only one who mentioned such incidents. Male gig workers on other applications, including Instacart and Uber, linked racial profiling a directly to their work. The orders they accept are informed by their knowledge of the physical and emotional risks of navigating the world around them, a world in which racialized cultural systems have justified the criminalization and surveillance of Black bodies. The risks associated with being racially profiled continue to exist even when platform workers log into the platform application for work. Logging into the app does not equal logging out of the reality of structural racism.

Anderson and John perceive racial profiling as more than an emotional stressor, viewing it as a physical risk of on-demand platform work. As demonstrated by Jacinta Gau and Kareem Jordan, the socially constructed belief that Black bodies should be surveilled or “supervised” is a historical development of structural racism.[17]Gau and Jordan, “Young Black Males, Suspicion, and Surveillance,” 8–15. The emergence of platform technology has amplified the extent to which workers’ bodies are surveilled within the platform economy. Workers’ behavior and actions are surveilled by both in-app functions and by White individuals who deputize themselves as agents of racial control.[18]Bonilla-Silva, “Feeling Race,” 10. Even individuals who consider themselves antiracist can engage in racial profiling. Take, for example, the words of social justice writer Rebecca McCray, who, in reflecting on her own racialized fears, wrote:[19]Rebecca McCray, “What McKinney Says About White American Fear of Black Citizens,” TakePart, June 9, 2015, … Continue reading

“While it is my job to think and report deeply on race and justice in my waking life—by the way, I’m a White woman from a predominantly White Midwestern city—I have also instinctively, and unthinkingly, clutched at my purse while crossing paths with a black man on a dark street, then felt disgusted at my actions. I have locked my doors while driving through the South Side of Chicago.”

For Black workers operating in the platform economy, racial profiling not only shapes which tasks they accept, but how they complete them. For example, DoorDash driver, Charles, told me: “I don’t wear hoodies, and I am always sure to have something that has the DoorDash logo on it, and I’ll wear my undergraduate university shirt, so they know I’m not a threat; I’m supposed to be here.” To prevent activating racialized emotions of fear and distrust, reinforced by stereotypes of Black youth as inherently criminal, Black platform workers operate under the assumption that they are always under surveillance.[20]Scott W. Duxbury and Nafeesa Andrabi, “The Boys in Blue Are Watching You: The Shifting Metropolitan Landscape and Big Data Police Surveillance in the United States,” Social Problems 71, no. 3 … Continue reading If you are constantly under surveillance, what you wear and how you dress is incredibly important. According to the company’s website, catering bags with the official Uber logo range from $12 to $16, with entire safety kits that include vests ranging from $16 to $38.70. Despite the added cost, all of the Black platform workers I interviewed stated that they carry some sort of item signaling that they are working for Uber (e.g., window stickers), Lyft, DoorDash (e.g., freezer bags), and Instacart.

Racial profiling carries a cost. Black platform workers are tuned into the real and material consequences of racial profiling and are constantly faced with finding new ways to protect themselves. “Whites acting as deputized agents of racial controls”[21]Bonilla-Silva, “Feeling Race,” 10. have always been a part of the fabric of racial capitalism; however, within the platform economy, these “deputized actors” are given the power to directly impact the income and the behavior of platform workers. Acting with hypervigilance has always been an embedded part of the working conditions for Black workers, but platform technology often makes invisible the material and mental health consequences of navigating racialized surveillance.

Conclusion

The shifting of rideshare and service work onto platform applications has not changed the extent to which gig work is shaped by pre-existing structures of racism. Instead, the narrative surrounding platform technology has made it more difficult to hold companies liable for the way they benefit from racialized emotions. Given the risks and potential negative impacts on mental health, platform workers should have the opportunity to receive compensation and benefits from platform application companies. Yet, platform applications’ assertion that they are “digital intermediaries,” not employers, allows them to shift the responsibilities and risks of “platform work” onto workers. Due to a lack of federal protections, platform workers are considered independent contractors rather than employees of platform application companies. Thus, platform application companies like Uber and DoorDash are not held responsible for evaluating and addressing the well-being of gig workers. Take, for example, the incident mentioned above regarding the Uber driver Wesley Gakuo. In response to the 2022 incident, Uber shifted responsibility onto the driver by arguing that they are not responsible as digital intermediaries, stating that gig work is precarious and unpredictable. The claim that platform companies are not employers allows them to escape culpability for potential physical and mental harm to individuals working on their platforms. By centering the experience of Black platform workers, we can better understand the shortcomings of the platform labor economy, aiding labor advocates who are calling for platform companies to protect gig workers better, as well as demand policymakers to classify workers as employees.

Footnotes