Reels of Resistance: Black Archiving in Digital Spaces

Reels of Resistance: Black Archiving in Digital Spaces

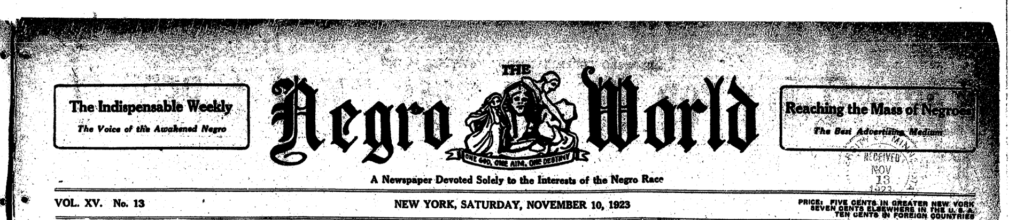

The year is 1923, and you just paid a nickel for the latest edition of the Negro World, the flagship newspaper of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). Opening to the “The News and Views of the UNIA Divisions” section, you read “Port Limon Celebrates International Holiday.” This headline introduces an article reporting on the celebration of the African diaspora in Puerto Limón, Costa Rica. It describes the participants of the parade, including the youth, the Black Cross Nurses, and the Universal African Motor Corps, who then all gathered in the evening for a series of speeches, a grand bazaar, and a garden party. Now, had you opened Instagram on August 31, 2025—over a hundred years after this article was published—you could have seen photos and videos documenting the Grand Gala Parade in Limón. Taking place on “Day of the Black Person and Afro–Costa Rican Culture,” the event celebrates Afro–Costa Rican identity and history, culminating with a grand parade. The continuity of these two events across a century have and are being documented and maintained by local organizations, such as Solo Nos, with missions to respect and celebrate the contributions of the African diaspora in Costa Rica. Historically marginalized from institutions because of segregation, anti-Blackness, and colonialism, Black communities across the world have relied on powerful forms of heritage preservation through community archives and documentation. In the case of the UNIA, this took the form of the New Negro newspaper; in the case of Solo Nos, it’s taking the form of online content.

A crucial characteristic of these forms of archiving is the incorporation of oral history, art, and other formats that originate from within the community. Just as the goals of the UNIA have persevered into the twenty-first century, so have the methods of self-archival practices. The emergence of accessible technologies like blogs, vlogs, zines, and social media introduced new perspectives and global connections but also have led to an oversaturation of content online. Here, however, I explore how these forms of technology mirror a space for self-defined narrative and employ Black archival practices that have been utilized for generations, using Solo Nos as an example. This will provide a contextual foundation for the importance of Black community organizing in preserving history and celebrate how that looks now—even if it may be unconventional.

Those marginalized or taken advantage of by institutions find alternative ways to inform themselves and preserve their own narratives.[1]Laura E. Helton, Scattered and Fugitive Things: How Black Collectors Created Archives and Remade History (Columbia University Press, 2024). Black archives have taken shape in many ways, such as scrapbooks, art forms like the blues, and, more recently, blogging.[2]Noah Lenstra and Abdul Alkalimat, “eBlack Studies as Digital Community Archives: A Proof of Concept Study in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois,” Fire!!! 1, no. 2 (2012): 151–184, … Continue reading Digital spaces mirror and expand on the ways communities have empowered themselves for generations. The UNIA, the largest Black organization of the twentieth century, presents a great example of the power of self-archiving and documentation as a tool to preserve heritage.

Founded in Jamaica in 1914 by Marcus Garvey and Amy Ashwood, the UNIA aimed to unify the African diaspora and promote agency within Black communities. The slogan “Africa for the Africans, at home and abroad” exemplifies their focus on Pan-Africanism and desire for autonomy. The UNIA pursued these goals, in part, through reclaiming education and utilizing its own resources to maintain and protect its own information.[3]Richard Iton, In Search of the Black Fantastic: Politics and Popular Culture in the Post-Civil Rights Era (Oxford University Press, 2008). However, like many other leading Black organizations throughout history, the UNIA was subject to misinformation and false narratives, including being heavily monitored by the Bureau of Investigation (the precursor to the FBI). Their archives allude to Garvey being a “racial agitator” and reveal specific efforts to portray the UNIA as a dangerous organization. The UNIA relied on its internally run newspaper, the Negro World (see Figure 1), which was founded in 1918, to connect Black communities and document the organization’s activities globally. The Negro World provided a space to celebrate the work of the UNIA’s chapters and members across the diaspora. Every issue shared news from across the Caribbean, throughout the United States, to continental Africa and beyond. This active archiving of the organization gave the UNIA the power to tell its own history.

Since the newspaper and social media have both acted as real-time archives of movements’ actions and goals, it is relevant to pay attention to how organizations are self-archiving in order to advance the autonomy of their communities. Thanks to the Negro World, we can get insights into local community events like the Port of Limon parade in 1923. In the present, Solo Nos is one organization that exemplifies this self-archiving.

Based in Puerto Viejo, Costa Rica, Solo Nos was founded in 2012, and their mission statement asserts that “Solo Nos is not just an organization, it’s a movement. It’s the product of a belief that we are not dependent on external influences to solve our communities’ needs.”[4]Solo Nos, https://solonoscr.com. Or, in short, “By the community, for the community.” At the helm of Solo Nos is Velvet Waite Hines, alongside her son Chris Waite Sanders. She leads initiatives to protect the Afro–Costa Rican and Indigenous identities in the area, both culturally and politically. Solo Nos is an example of how preserving narratives exists outside of institutions like universities and government agencies, and how art, music, and social media all tie together to protect the community. Solo Nos is inspired by the teachings and goals of the UNIA, a legacy of the latter’s work a century earlier. They promote Pan-Africanism through education, the protection of resources and heritage, and cultivation of community. Waite brings the community together, speaks on complex issues, and stands up for local interests, most recently that of land rights for Afro–Costa Rican and Indigenous communities in the area. Solo Nos members, including Queen Velvet and her family, led the Puerto Viejo parade in 2025, as seen in figure 2.

Jewell Ruth-Ella Humphrey.

Solo Nos maintains its history by honoring and acknowledging their community’s founding generations. Through community events, such as the annual Sankofa Festival and teach-ins, the organization fosters interaction between generations. These activities not only provide care to the community but offer a place to preserve culture. The Liberty Hall where these events take place is filled with photos of important historical events, community members, and other images of cultural significance, making it a growing archive for the community. On the technology front, Solo Nos is very present on social media platforms. In one Instagram Reel posted by the organization, Queen Velvet sits with her mother, Yolanda, and aunt Loretta as they discuss matters such as land rights and tourism. This interview took place at an important Black business in the community but was also livestreamed on social media. This extends a new life to the preservation of moments, particularly as these media can reach the younger generation, some of whom live or study abroad. The events of Afro–Costa Rican Heritage Month were also shared via social media, allowing for a space for conversations initiated from within the community to take place.

As forms of information sharing evolved over time, reliance on newspaper led to radio and television news, magazines and zines, blogs and vlogs, and now social media. The ability to create and consume content has grown rapidly. Acknowledging social media and digital media as part of a longer lineage of archival practice places it in a realm beyond the sea of information threatened by artificial intelligence, misinformation, and false narratives. Through hosting conversations via Instagram Live, Waite holds the community accountable to staying informed and involved. Using Instagram Reels and blog posts, she documents the happenings of Puerto Viejo and archives the work of Solo Nos. Queen Velvet also performs at local events, using her voice and fashion to express her identity unapologetically. Recognizing all of these to be forms of archive and truth-telling can deepen our understanding of what it means to preserve heritage.

The UNIA and Solo Nos are examples of how preservation of truth, culture, and identity can take place on the community’s terms. The constant changes in how Black communities self-archive in digital spaces present numerous opportunities, such as Solo Nos’s ability to reach a widespread audience while maintaining the integrity of its messaging.

Black digital humanities research uses technology as a tool for recovery.[5]Kim Gallon, “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities,” in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, ed. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 42–49. Solo Nos and other dedicated groups are using social media platforms to recover the power of knowledge previously wielded by griots, various art forms, and newspapers. Using creative outlets like short films, reels, music, and art workshops, Solo Nos preserves cultural significance. As we continue to see technology develop, I ask, how will the limitations of truth telling change? What is the balance between ease of access to information and intentional gatekeeping? It is essential to consider how to both acknowledge and safeguard those efforts in digital spaces today. While technology is ever-changing, safeguarding can look like continuous efforts to find new and relevant ways to include the newer generations in tradition and education.

Leading organizations such as Solo Nos use everything at their disposal to preserve their narratives outside of mainstream institutions. As Waite calls on by using the Twi phrase sankofa, meaning “go back and get it,” these digital archival methods not only “go back and get it” but also push the boundaries of what digital spaces mean for community building and the future of technological archiving. From Sammie’s reel guitar in Sinners (2025) to Queen Velvet’s Instagram Reels, Black archives have always thrived outside of institutions, and it is exciting to consider how that will continue to develop. This work of celebrating the contributions of Black organizations and their archival practices serves as a reminder that the goal of maintaining truth and narratives takes many forms. As we devote so much time to consuming content online, we should consider the ways in which the information we consume can be part of a larger legacy of preserving identity.

Whether you are an organizer, community member, professor, writer, or otherwise, consider the following: How might you support the maintenance of truth within your own community? How might you have overlooked forms of archive in art, social media, or other platforms due to institutional marginalization? As the forms of truth telling change, so must our approaches to teaching, sharing information, and learning. For better or worse, the digital world is constantly changing, which benefits information sharing but also poses a threat to both the lifespan and integrity of digital information. While it may grow increasingly difficult to discern between different types of reliable information, it is truly an act of love to document and preserve history just as people always have. I look forward to future adaptations.

Footnotes

| ↑1 | Laura E. Helton, Scattered and Fugitive Things: How Black Collectors Created Archives and Remade History (Columbia University Press, 2024). |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Noah Lenstra and Abdul Alkalimat, “eBlack Studies as Digital Community Archives: A Proof of Concept Study in Champaign-Urbana, Illinois,” Fire!!! 1, no. 2 (2012): 151–184, https://doi.org/10.5323/fire.1.2.0151. |

| ↑3 | Richard Iton, In Search of the Black Fantastic: Politics and Popular Culture in the Post-Civil Rights Era (Oxford University Press, 2008). |

| ↑4 | Solo Nos, https://solonoscr.com. |

| ↑5 | Kim Gallon, “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities,” in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016, ed. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren F. Klein (University of Minnesota Press, 2016), 42–49. |