“No Data About Us Without Us”: An Afrofuturist Reflection on Digital Liberation

“No Data About Us Without Us”: An Afrofuturist Reflection on Digital Liberation

Schools and public institutions are increasingly adopting data-driven surveillance technologies that deepen carcerality and social control in the lives of marginalized youth. This essay draws on the No Data About Us Without Us Fellowship, a program of the NOTICE Coalition: No Tech Criminalization in Education and the Edgelands Institute. The fellowship convened grassroots organizers, educators, youth activists, and community leaders to examine how digital surveillance technologies are reshaping school discipline and to explore transformative alternatives that reduce harm and protect the rights and freedoms of youth and young adults.

Who do you call when AI labels your child a criminal?

By the time Tammie Lang Campbell answered her phone to speak with the distraught family, their 14-year-old child had been locked in a central Texas juvenile detention facility for three days. In September 2024, he’d been arrested during his first-period class—handcuffed at school, taken without his parents’ knowledge, and sent to a prison for children. His charge? Making a joke on social media that authorities deemed a “terroristic threat.”

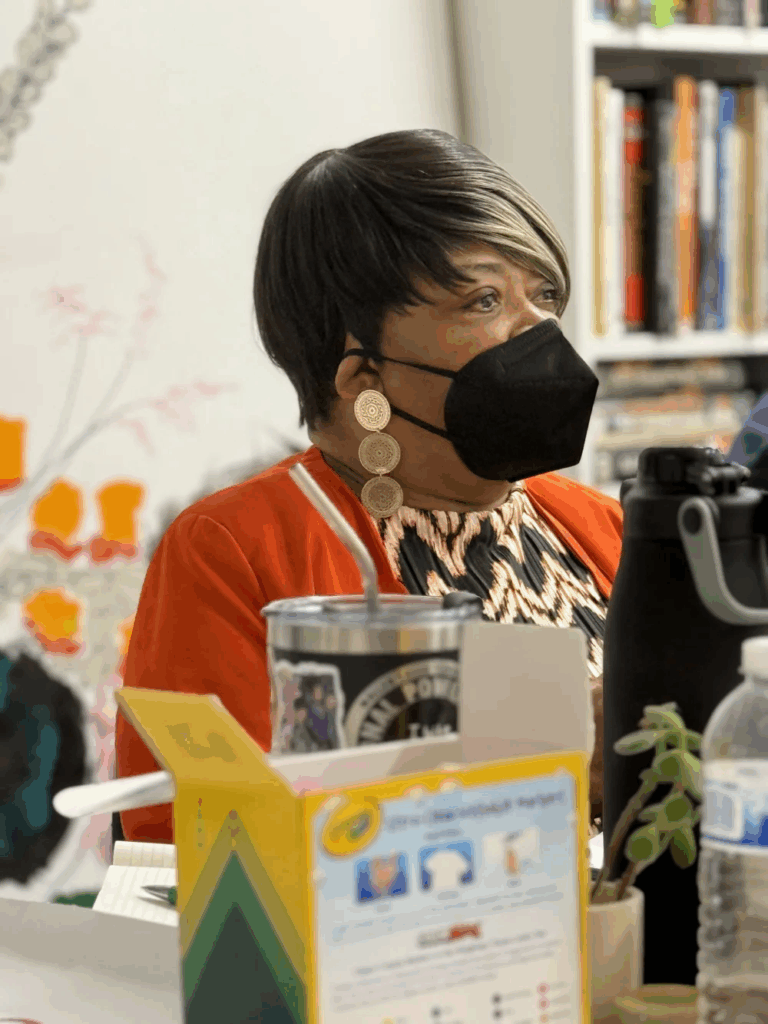

For Tammie, founder of the Honey Brown Hope Foundation and a longtime advocate for Black families navigating the harsh terrain of school discipline, much of this story was disturbingly familiar. For years, she had stood on the frontlines with families, helping them protect their children from the school-to-prison pipeline.

But this time felt different. This case wasn’t just another example of discriminatory discipline. It was a warning sign. A new frontier. And for Tammie Campbell, it was confirmation that the systems she’d been fighting for decades were evolving in insidious ways through digitized surveillance.

“The surveillance, the monitoring of students, that’s not new,” Tammie explained in an interview with the Edgelands Institute, “What is new is the data-driven technology that’s being used to advance the school-to-prison pipeline and how it’s being used under the guise of school safety and technology advancement for students to be able to compete in a global society.”[1]Interview quote derived from fieldwork archives that are on file with the authors of this essay. The interview was conducted by Chelsea Barabas and Rian Crane at the beginning of the NDAUWU … Continue reading

Over the next six months, Tammie would unpack the implications of this experience through a new initiative called the No Data About Us Without Us Fellowship (NDAUWU). During this fellowship, Tammie collaborated with other organizers and local leaders across the United States to investigate how racialized patterns of school policing, punishment, and pushout are rearticulated through digital technologies. Together, they developed creative tools and charted new ways of imagining how technology could support young people’s well-being in the digital age, while disrupting the cycles of punishment and exclusion that shape their lives. This essay kicks off a series of reflections that situate the fellowship within an Afrofuturist tradition—treating the work as both archive and portal, a set of stories that illuminate how communities are already practicing freedom in the face of surveillance.

The Rise of AI Surveillance

What Tammie saw last fall in Texas is part of a sweeping transformation in policing and public education—one that mirrors a broader pattern across critical public services and social safety nets nationwide. Artificial intelligence and algorithmic decision-making are being embedded into institutions that shape our daily lives, from classrooms and courtrooms to clinics and welfare offices. Under the banner of “innovation” and “efficiency,” these systems often intensify existing inequalities, deepening the reach of carceral logics into spaces once imagined as protective or supportive.

In schools, AI surveillance has rapidly become a core part of this shift. Districts are adopting big-data policing tools and predictive analytics that extend the school-to-prison pipeline and normalize constant monitoring of young people.[2]Clarence Okoh, Dangerous Data: What Communities Should Know about Artificial Intelligence, the School-to-Prison Pipeline, and School Surveillance (Center for Law and Social Policy, 2024), … Continue reading As Ruha Benjamin describes in Race After Technology, this is the “New Jim Code” in action: new tools reproducing and amplifying racial injustice under the guise of technological progress.[3]Ruha Benjamin, Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Polity, 2019). Far from neutral, these systems entrench patterns of exclusionary discipline, criminalization, censorship, and public divestment—now turbocharged by automation.

These harms are tangible. In Florida, a district partnered with police to build secret databases of “at-risk youth,” using algorithmic risk scores to label children “destined for a life of crime.” In Massachusetts, a school shared sensitive student data with immigration authorities through an interagency data-sharing program. Across the country, AI-powered monitoring tools have triggered involuntary psychiatric detentions of children flagged for certain keywords online. Even school bathrooms have been turned into surveillance sites,[4]Ellie Spangler, Clarence Okoh, and Marika Pferfferkorn,cAutomating School Surveillance: How Student Vape Detection Technologies Threaten to Expand the School-to-Prison Pipeline in Minnesota and … Continue reading with AI-enabled sensors and microphones deployed in Alabama, Texas,[5]Chelsea Barabas and Ed Vogel, Houston Diagnostic Report (The Edgelands Institute, 2025), https://www.edgelands.institute/outcomes/houston-diagnostic-report. and Minnesota to detect and punish students for vaping and bullying.

These are not isolated cases. A national survey of 3,000 teachers found that nearly 90 percent reported at least one form of AI surveillance in their schools, with usage even higher in high-poverty districts. This explosion has been fueled by a multibillion-dollar surveillance industry and increased public funding for public safety in the wake of recent acts of school violence. The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act is one such funding stream that includes $300 million for data-driven school surveillance strategies and school hardening strategies.[6]Deanie Anyangwe and Clarence Okoh, The Bipartisan Safer Communities Act: A Dangerous New Chapter in the War on Black Youth (Center for Law and Social Policy, 2023), … Continue reading

Schools are not alone. Across the United States, AI is increasingly woven into the infrastructure of welfare programs, housing authorities, immigration enforcement, and public health—institutions that determine who receives support, who is punished, and who is excluded. From “child welfare” algorithms that separate families to Medicaid fraud detection tools that wrongfully deny care, the same technologies driving student surveillance are being used to police and control the most vulnerable in every corner of public life.[7]See Virginia Eubanks, Automating Inequality: How High-Tech Tools Profile, Police, and Punish the Poor (Macmillan, 2018).

Grassroots Resistance to Algorithmic Oppression

Across the country, a growing network of grassroots coalitions is answering the rise of AI surveillance with creativity, persistence, and solidarity. Rather than treating algorithmic harm as a series of isolated glitches, they are confronting it as part of the same oppressive systems they have worked to dismantle for a long time.

Labor organizers are facing off against tech giants like Amazon. Climate activists are challenging companies like xAI that pollute Black neighborhoods. Legal aid attorneys are defeating algorithms that deny people access to Medicaid. Youth justice advocates are exposing “child welfare” risk models that separate children from their parents. And across the country, activists are erasing gang databases, canceling municipal surveillance contracts, and winning legal protections that expand constitutional rights in the digital age.

This emerging movement is not only resisting harm—it is also imagining and enacting alternatives. If oppressed peoples’ dreams of freedom are to survive Big Tech’s dystopian designs, we must rely on a different set of principles to sustain and grow our resistance tradition, concepts such as mutuality, solidarity, and ancestral intelligence.[8]Aymar Jèan Escoffery, “Ancestral Intelligence: The AI We Need,” Commonplace, October 30, 2023, https://doi.org/10.21428/6ffd8432.6bf7b4ae. We have come to understand these practices under the umbrella term of Afrofuturism. Often described as a speculative or aesthetic practice, Afrofuturism has always contained practical and political dimensions that inform how advocates respond to the conditions of racial oppression and create spaces for possibility outside the limitations of the present.

The NDAUWU Fellowship was our experiment in building community infrastructures for Afrofuturist world-building in the digital age. We drew inspiration from the Black radical tradition of fugitivity—the refusal to be confined by systems of domination, and the constant search for life beyond their terms. For us, fugitivity was not about escape or withdrawal, but about moving through the grip of these systems on our own terms—finding cracks, creating openings, and refusing to be defined by their logics. Along these ragged edges of algorithmic power, the fellowship carved out spaces where different futures could take root. Here, freedom was not something deferred to a distant horizon, but something practiced in the present, cultivated in defiance of the systems that seek to contain it.

The NDAUWU model was first designed by the Twin Cities Innovation Alliance (TCIA) to empower parents responding to algorithmic oppression in Minnesota public schools. Building on that foundation, the NOTICE Coalition and the Edgelands Institute expanded the model to a national scale, convening an intergenerational cohort of youth justice advocates, educators, artists, and civil rights organizers from Houston, the Twin Cities, and Chicago. Together, they investigated how racialized school policing and pushout are being rearticulated through emerging technologies—and how communities might imagine alternatives.

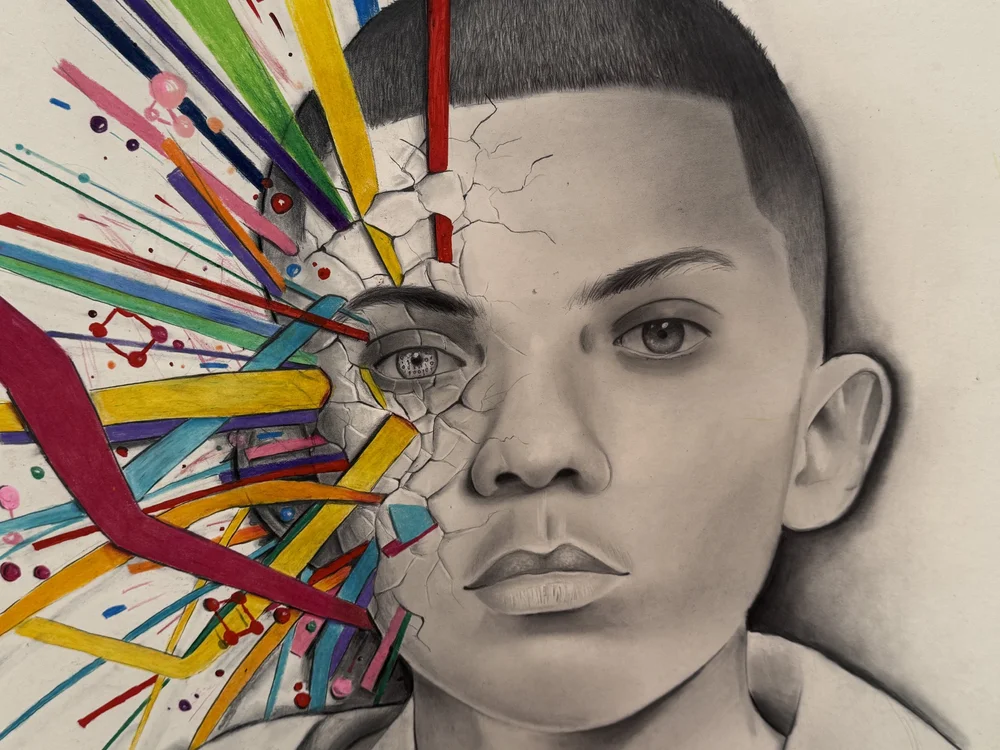

Over several months, the fellows used creative and cultural organizing—poetry, puppetry, portraiture—not just to critique harmful systems, but to invite broader participation in reimagining them. The projects they created—digital justice workshops, community research,[9]Barabas and Vogel, Houston Diagnostic Report. and youth trainings—helped seed new visions of the role of technology in the future of education.

Yet work like this is fragile. Philanthropic support is scarce, policymakers’ attention fleeting, and Big Tech continues to capture the very agencies charged with accountability. These pressures make it all the more urgent to share what was built through NDAUWU, so the lessons, tools, and visions generated here can travel and take root elsewhere.

By grounding their analysis in lived experience, drawing on Afrofuturist traditions, and working collectively across geographies, the fellows modeled what it means to “flip the script” on injustice—transforming surveillance’s peripheries into spaces for freedom in the digital age. Their work reminds us that our communities will need to build grassroots infrastructures that connect movements, extend resources, and amplify impact, so local struggles can strengthen one another in the fight against algorithmic oppression,[10]Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (NYU Press, 2018). mass surveillance, and data capitalism.

Building Together

The NDAUWU Fellowship was a rare and vital experiment. It broke from the narrow, technical, and reform-oriented conversations that so often dominate debates about technology and education, centering instead the knowledge and imagination of those most impacted. By combining political education, creative practice, and cross-geographic solidarity, our cohort charted new possibilities for resisting surveillance and reclaiming technology for liberation.

At the heart of the fellowship were eight organizers, artists, and educators who committed to growing local infrastructures to contend with the rise of algorithmic oppression in the lives of young people. Their stories ground the fellowship’s vision in lived experience. Among them was longtime Fort Bend advocate Tammie Lang Campbell, whose journey illustrates both the urgency of the problem and the promise of this work.

When Ms. Tammie picked up the phone that day, she was answering more than a call from one family in crisis. She was answering a challenge that communities across the country now face: What do we do when the systems meant to protect our children instead criminalize them, aided by new tools of digital control? The fellowship was one answer. This essay series is another—an invitation to carry forward the lessons, tools, and visions that emerged from NDAUWU, and to build together the infrastructures we need for freedom in the digital age.

Editor’s note: This essay is the first in the Storytelling Project essay series, which shares the lessons and visions that emerged from the No Data About Us Without Us Fellowship hosted by the Edgelands Institute and the NOTICE Coalition: No Tech Criminalization in Education. The authors of this piece are two of the leaders in the NOTICE Coalition who were part of a larger team that facilitated the fellowship program.

Future essays in the series are available here.

Footnotes