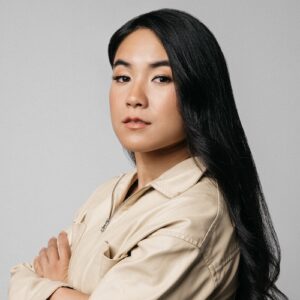

A New Perspective on Gen AI in Art Practice: A Conversation with Michaela Ternasky-Holland

A New Perspective on Gen AI in Art Practice: A Conversation with Michaela Ternasky-Holland

As generative AI technologies proliferate in the arts and filmmaking, many creatives have pushed back and criticized its ever-increasing use. However, some view this development as an opportunity. In this conversation, Just Tech Program Officer Ever Bussey talks with director and artist Michaela Ternasky-Holland about her art practice and how generative AI can help innovate art.

Ternasky-Holland is a Peabody-nominated and Emmy award-winning director who uses immersive and interactive novel technologies, like generative AI and virtual reality, to create impactful stories. She is one of the first directors to create and premiere a short film utilizing Open AI’s SORA platform, which screened at the Tribeca Film Festival. She has won multiple awards, received numerous accolades, and her work has been exhibited at various institutions, including the New York Public Library, Museum of the Moving Image, and Venice International Film Festival.

Ever Bussey (EB): Thank you, Michaela, for taking the time to do this. I wanted to begin by asking, what made you want to pursue art and film?

Michaela Ternasky-Holland (MTH): In high school, I was heavily involved in dance and performance. I really loved the theatricality of being on stage and I loved being able to put people into an experience and allow them to follow along with the story using modalities like dance or dramatic performance. Though I sort of knew deep down I probably didn’t want to get a college degree in dance or dramatic performance, I wanted to continue the storytelling that I enjoyed doing. I told my parents that I wasn’t going to apply to college, and they took me out of performance and basically gave me an ultimatum: until I applied to university and to degrees that they approved of, I wasn’t going to continue dance.

So I was forced into this traditional university route. I wanted to find a college in Southern California, close to Los Angeles, and I wanted to try and find a degree that was going to enhance this storytelling I had been doing. I found that at the literary journalism program at UC Irvine. But even while I was there, I always had one foot in university studies and one foot in professional performance. That came to a head when I booked a contract with Disney Cruise Line to work and perform for nine months, putting my college studies on hold. And it was one of the best decisions I made for myself, because it really gave me a lot of insight into not just guest experience design and overall immersive performance, but it also gave me a level of quality and grit that helped me realize that even if I work every day with no breaks, I can make something I’m really proud of.

I really got to hone my work ethic and sense of accomplishment and pride being on the cruise. I also started exploring other modalities of storytelling. I would use my GoPro to make little GoPro videos and teach myself GoPro editing, and then I would write newsletters to people back home to let them know what I was doing on the contract. I was training different muscles. Going back to finish my university degree was one of the hardest decisions I made, because I was offered another cruise contract. But, when I went back to college, I promised myself to find the same level of enjoyment I had in the cruise, but maybe do it in a way that incorporated literary journalism and long-form storytelling.

So, I really got to explore storytelling and my own passions and interests in both school and in professional performance. I’ve done my best to merge those two things together in my career, which I’ve been able to do through immersive experiences like using virtual reality, using new technology like artificial intelligence, or utilizing physical design through immersive or interactive installations. I really feel like I can express the spectrum of my passion and the spectrum of my experiences through my art and through my work.

EB: How do you think your form of art and filmmaking is unique from that of others?

MTH: One thing that makes me unique is that I didn’t identify as an artist or as a creative for a very long time. When I graduated from college, I tried to identify as a digital journalist or as a journalist who specialized in emerging technology. Working at Time magazine, that label and that industry felt too narrow and too limited for the expansive, more social-justice-oriented work I wanted to do. For a while I even identified as a documentary creator or a social impact creator or producer. In the last few years, however, I’ve begun to fully embrace this idea of creating and making things for myself with my name at the top that I realized what I do is really artistic and creative, and so even the title of director is something very new for me to take on as a role in my projects.

Even though the work I do isn’t necessarily directly impacting or related to filmmaking, it has a lot of aspects of filmmaking, and even if a lot of the work I do isn’t directly inside the art world, there’s a lot of what I do that has been influenced by art practice. By using these titles and terms that we associate with fields like art and filmmaking, I’m trying to find my right association. So, sometimes I would say this is more art-like or more film-like, but it’s still an all-encompassing way of describing what I do, unless I use terms like multidisciplinary or multimodal or multifaceted. That’s what I have always enjoyed—it’s never one road, one path, one way of doing it. It’s always mixing and playing, taking different life experiences, different stories, and different things and mixing them, not just the genres and the mediums and the styles, but even the execution as well.

EB: I think that’s been a theme that I’ve noticed about you since I’ve met you. This kind of “figuring it out as I go” is the experimental approach that you have. Through witnessing your work and listening to how you talk about your work, I recognize that you do appreciate that quality about yourself. I also have had conversations with you where you’ve mentioned a kind of frustration with the lack of support that you get from other institutions. Can you speak to that frustration or that contradiction?

MTH: What’s so interesting is that I’m very blessed and lucky to have had my work recognized by many institutions and have received very predominant accolades. Yet, when I try to apply to opportunities at more traditional institutions, because I want to learn more about traditional settings, such as a more artistic residency, or performance art residency, or a filmmaking fellowship, I tend to find that all of these spaces don’t see me. Instead of seeing me potentially as an asset, as somebody who has done so much to encourage and motivate herself to try new things and expand her horizons, and as someone who takes aspects of performance art, traditional art, and filmmaking and blend them, into her work, it always comes down to my work samples not meeting their criteria. I don’t have the x piece of material that they’re looking for to validate my work.

Despite the fact that the institutions they seek validation from, such as the Emmys, Peabody Awards, or Producers Guild of Innovation, or on the flip side, curation at a museum like the Museum of the Moving Image or the Nobel Peace Center, are the end goals where they would want to see their residents or fellows or program attendees be able to get to by the end of their fellowships and programs and even toward the middle of their careers; it’s like they’re only wanting to see it from a very specific angle. It often frustrates me, because it is already very hard to continue to build momentum in an experimental space. Even though traditional institutions say they want to have innovation and newness and inspire the next generation or the next phase of their industry, they continue to close their doors or shutter their opportunities to you, which feels like they’re saying one thing and doing another.

EB: This likely will be related. When we spoke two weeks ago, you mentioned that you were excited about the disruption that gen AI brings. This contrasts with how other artists feel toward emerging tech, obviously not all artists, but a lot of them. One example is the tension as it relates to Hollywood and the strikes that took place and the precarious position that artists were put in as this larger industry turns to rely more on generative AI. Can you expand on what’s exciting about this disruption, and how you connect to the tension of what is lost with gen AI?

MTH: There’s always a context to when or how I or someone else uses technology. However, I don’t have a deep background in Hollywood, so that isn’t my context. I do think it is the responsibility of large corporations to take their interest beyond the bottom line and their profit margins and look at how some of those decisions actually impact people’s lives.

I am not saying I’m all for using these new technologies to propel capitalistic motives that we’re already seeing as having very harmful impacts. What I am seeing on the other end of this context is artists and filmmakers who are struggling to have their voices heard, financed, and accepted. This technology, especially right now when it’s new and before it becomes expensive, can really help give artists opportunities to make their art and to be seen without needing the validation, acceptance, and funding from other institutions that might be overwhelmed.

Another piece of the puzzle is about how a lot of people want to be creative, want to make their art, and want to be filmmakers. But what’s keeping them from pursuing these goals is not necessarily education, because now we have the internet or access to certain technology because everyone has 4K phones in their pockets. It’s this feeling of not being able to find the right environment of support and collaboration, even the right kind of opportunities, for them to express their art how they envision it. With generative AI I think there’s a strong possibility that it can help bridge that gap. But right now, we’re going through an uncomfortable, contentious transitional period, and I recognize that that means there’s going to be a lot of moments of people lashing out against one another. There’s going to be a lot of people who have very strong opinions about it, and I think that’s very good and healthy for the industry.

We’ve gone through many creative revolutions before, such as the introduction of the printing press, the introduction of photography, the introduction of digitization in filmmaking. Gen AI is another big step for us. What we need to do is educate creatives on how to use these new tools so that we are more informed with what they can and can’t do, but also how these tools are or are not uplifting ethical productions of art, whether that’s the input or the output of these systems, and how these systems collect data. There’s a lot that we as creatives can do to get involved, but you can’t get involved if you’ve never actually played with the technology. You can’t shape your future if you’re not an active party in that future.

EB: If I’m not mistaken, you have worked with or consulted for tech companies and other production companies on gen AI and your use of it. I’m wondering about the nature of that consultation. Is it forecasting specifically? Do they want to know what you think they should look out for? What are you finding in these rooms? And what do they want to know from you?

MTH: Those are great questions. First and foremost, I think everybody still is a little bit confused about how to use gen AI and how it can be employed for their specific use case scenarios. In some cases, it’s people or organizations that are like, “Hey, we want to understand what level of quality we can get for this work if we give you this budget and this level of support.” They need somebody who’s gone through the process to be able to say, “Well, this is kind of the quality you’re looking at.” Or “we can host something like this internally and you can see for yourself the resulting quality or timeline and the budget or the process that’s needed.” And I can give them these forecasts and estimations.

I also advise on how they need to staff up for these kinds of productions, because one person can’t do the work, which, I think, is a big controversial form of propaganda that tech companies and some creators are perpetuating. I think that’s very harmful to the work because it’s still very similar to creative work. It takes incredibly talented people and very collaborative teams to make the best work. So, I’m constantly advising on and displacing rumors and preconceived notions and really try to showcase the possibilities and realities.

People are asking me for my advice on what systems of change or what possibilities or what can we do to predict where all this is going. Whether that’s the idea of putting together packages to license data to certain tech companies, or another idea of verifying data is based on real humans rather than synthetic data.

Many creatives and organizations are thinking about the future because they’re still wrapping their minds around the fact that gen AI exists and these tools are out there. Instead, they should be thinking about how to work today with these tools and prepare so that tomorrow they’re protected or understand how to economically participate in this arena. There’s a lot of things that aren’t as widely discussed that I help people think about and recognize that these are real possibilities coming down the pipeline.

EB: Michaela, whose work inspires you?

MTH: Well, that’s a great question. I find my inspiration in a lot of different spaces. I would say one is Rhizome’s recent exhibit down at WSA, Rhizome World. There are so many interesting analog technology pieces there, pieces that were using old systems, like old computers that were running on different processing systems that we haven’t seen in a while that kind of give you that throwback, nostalgic feeling. But really, I find a lot of my inspiration in reading. I really enjoy reading science fiction and fantasy that examine who we are as a people today. Some of these books are Atomic Habits by James Clear, Playing Big by Tara Mohr, anything by Louise Hayes, The Creative Act: A Way of Being by Rick Rubin, Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin, anything by Rick Riordan, and The Arc of the Scythe series by Neal Shusterman.

EB: What’s something you are working on that people should look out for?

MTH: A lot of people are interested in the input and output of generative AI, which I think is really valid. Where is the data that we use to train these systems coming from? What can I make when I put these things, like videos and photos, through these systems? I’m very interested in the actual act of generative AI as a mode for storytelling. Recently, I made an installation with Aaron Santiago, with whom I often collaborate, where we had people come into the space with cups of tea and they presented their tea to the Oracle. The Oracle gave them a bespoke astrological reading, using generative AI. You couldn’t see that it was made with generative AI, but this technology enabled us to create thousands of astrological readings—each between 20 to 30 seconds long—for these people with this really beautiful system.

For me, thinking about the use case of generative technology, for my next project, I’ve been thinking about—and I’ve been kind of seeing other artists start to move in this direction—what happens when you put generative AIs in live discussion and live debate with each other? How do they reflect our humanness? Or how do they reflect the gaps in our humanity? How do they reveal the things that we don’t even see in ourselves? How do they reflect the things we see in ourselves? That’s what I’m interested in seeing. In the current political landscape, what would happen if a group of audience members cocreated three political candidates using generative AI, then had those candidates debate using audience questions, and then the audience voted for the candidate they felt was best?

How can we utilize our voices in a democratic system as themes and as playable systems within this experience as a kind of new way of thinking about performance art or as a new way of thinking about theatrical technology? These are some of the things that I’m very interested in exploring. For those who are interested in what’s next, what’s happening in the generative field outside of the “corporate tech industries,” I think a lot of independent artists are thinking about putting this tech and its capacity to show humanness on display, inside of an interaction, an installation, or a video game in ways that broaden the landscape of storytelling’s capabilities. Generative technology enables a much wider capability of human capacity, and it can even create playfulness and serendipity, and again, this idea of playful aliveness in a way that I don’t think we allow ourselves to do anymore because everything is so rote.

Before you go to a restaurant, you look up the menu. Before you get in a car, you have the directions. Everything is so laid out for you because technology enables us to have full control over our lives. But with these generative technologies, there’s something about the happenstance or the luck or the fortune-telling side of it that I think we are missing and we’re craving and we’re longing for in our art and in our technology. So, I’m excited to see how that blossoms and grows.

EB: There’s an optimism in the way you speak about the future and present of gen AI that I don’t find when I’m in conversation with others. I think this conversation will be refreshing to some and provocative to others in a way that I hope is enlightening for them.

MTH: Thank you. I try not to be fully positive. Again, I could talk a whole lot about the negatives of it, and I can talk a whole lot about the issues that we have, but when you start talking about those things, you kind of give power back to the companies that made this technology. And, unless I am going to be on Capitol Hill vehemently arguing against these certain policies, then for me it’s about how to be constructive. Everybody else is doing the work of recognizing the negative parts of these systems. How can I be constructive right now to help people see that there might be a positive future where we can integrate these systems into our lives and they don’t feel as destructive and as indicative of the “end of creativity,” as some people might paint it to be?

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.